Where there are officially no rangers, their services are all the more needed. Whether combating environmental crime, cooperating with locals in protected areas or providing information to visitors: The small number of state environmental inspectors in Moldova is not able to fulfil them all, let alone have sufficient equipment and training. This is why a volunteer organisation has set out to establish the ranger profession in the country.

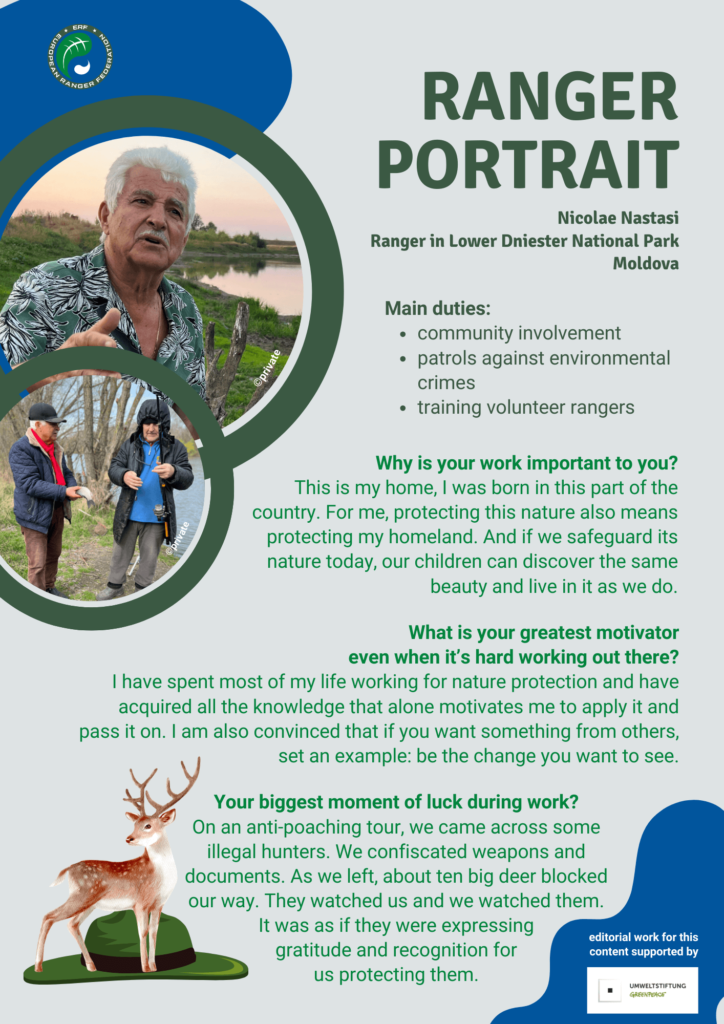

Petru Vinari and Nicolae Nastasi are working closely together to achieve this goal. While Petru coordinates the conservation projects of the NGO Ecological Society Biotica as a communications assistant, Nicolae uses his 25 years of experience as a chief state environmental inspector to train volunteers for the tasks of rangers in Biotica’s projects. In our interview, the two talk about how this increases the function of protected areas, where they stand on their joint path to establishing the ranger profession in the post-Soviet country and how the European ranger network is involved.

What is the current situation of the ranger movement in Moldova?

Petru: So far, the profession of ranger does not really exist in Moldova. However, there are state environmental inspectors, many of them volunteers, who work in nature reserves and prevent illegal logging, poaching, improper waste disposal and other forms of pollution.

We see the volunteers who have organised themselves

in the Lower Dniester National Park as future rangers.

We see the tasks of volunteer environmental inspectors in the long term as being similar to what in most European countries is called the profession of ranger, within a clearer legal and organisational framework. At the moment we have the Inspection for Environmental Protection as an institution. It offers opportunities for anyone who wants to volunteer. Together with Nicolae, we are working with a community of volunteer inspectors to protect the Nistrul de Jos – Lower Dniester National Park. We see them as future rangers, which is also the name under which they have registered their organisation: Organisation for Voluntary Environmental Protection Inspectors – Rangers. We are approaching state institutions in order to improve the organisation’s capacities and legal options.

What challenges does this volunteer project face in terms of nature conservation?

Petru: As a non-governmental organisation, we have been battling for the establishment of a national park for the last 26 years. Just 2022, the parliament approved the creation of the Lower Dniester National Park. So far, we don’t have an administration for this national park.

There is still no management for the national park. Only the NGO Biotica

draws up plans for effective nature conservation on behalf of the state.

All we have is our NGO, which is developing the management plans and projects for ecosystem services, monitoring, rehabilitation, community capacity building and water infrastructure. So we do a kind of parallel work for the state and work with different state institutions. And we think it’s better than nothing to engage these volunteers in practical conservation work on the ground, which we can integrate into a clear framework. Nicolae Nastasi leads the group because he has a lot of experience of what rangers should do in a national park. He was a chief environmental inspector in this region, which was declared a Ramsar site 20 years ago, a wetland of international importance under the Ramsar Convention. He works with like-minded volunteers and maintains his link with the state environmental inspectorate.

What is the need for rangers and what tasks do the volunteer state inspectors fulfil?

Petru: I got to know rangers during study trips to protected areas in Europe. I learnt that they are the guardians of nature reserves and form a bridge between people and nature – like a human right hand for nature. We urgently need this function in sufficient numbers to better protect our nature reserves in Moldova.

Nicolae: We have a good environmental law, but there is a lack of people to implement it. That’s why I decided to continue my work voluntarily after my retirement and monitor the Lower Dniester National Park area together with colleagues. Three state environmental inspectors are not able to cover the entire national park area of 60,000 hectares. I started working with Biotica when the national park was founded. 2022 I found 14 people to volunteer as environmental inspectors, last year there were 6 more. We cover the area of the national park and some villages in its district. Our main task is to monitor compliance with environmental regulations. On this point, I trained the volunteers with the help of a guide from Biotica for the tasks of volunteer environmental inspectors. We are also very aware of how people use natural resources.

As there are villages in the national park: How do you win people over to conservation?

Nicolae: First of all, we inform people that the national park is divided into zones where there are strictly protected areas, but also areas where agricultural activities are possible. We explain to them the rules of the park and that it is beneficial for them if the environment around them is protected. However, no commercial farming with pesticides is allowed near the river and other water sources.

Petru: There is no major loss of income due to the national park, as there is no administration and we as an NGO have not tried to change the utilisation of the land. However, we are in dialogue with farmers of large areas. Some of them are really interested in flooding their land to expand the wetland and receive compensation. But due to a lack of national priorities, progress is very slow.

How is the Moldovan ranger movement supported by the European ranger network?

Petru: We started this project together with the Czech NGO Arnika as part of a programme of the Czech Ministry of Foreign Affairs called Transition. Its main goal is to help countries make the transition from the Soviet era of conservation activities to the European standard. We have chosen Nicolae and the other volunteers to be responsible for the protection of the national park.

We want the state to provide the same level of

protection by rangers as in most European protected areas.

We don’t have them yet, but we want the same level of protection by rangers as in most European protected areas. That is what we want from the state. Our first model is Czech rangers, some of whom have already visited Moldova and talked to us about their experiences. We are also happy to have Romanian friends helping us to increase the capacity for future rangers. Therefore, I see the European Ranger Network as a tool for the development of the ranger profession in our country.

How many volunteer environmental inspectors are working in Moldova and what experience could they contribute as rangers to the European ranger network?

Nicolae: Official figures say that we have 30 to 40 volunteer environmental inspectors in the country. As this is not an easy job, sometimes even very risky, only 11 of the 20 volunteers who work with me are active. But they are very familiar with all the tasks of the state environmental inspectors, inform the public, go on patrol outdoors and are also on duty at night in urgent cases. The search for poaching or illegal fishing is the most dangerous task of the patrols. At the same time, we have a lot of experience in this area. And we hope that one day this can also be of use to other rangers in the European network.

Petru: In Moldova, there are some high-ranking people who commit such environmental crimes. They act as part of a big network, so they are not afraid of being prosecuted, but on the contrary they can promise punishment to the environmental inspectors or attack them in other ways. Such people were also the reason why the national park was not established for a long time. The World Bank gave money for the establishment of national parks in 2000, but Moldova had to pay it back because the park was not initially established. The first national park, Orhei National Park, was only founded 13 years later. And after 22 years the Lower Dniester National Park, for which we are working.

editorial work for this

content is supported by