When locals themselves take an active role in nature conservation, they become the greatest advocates for the protection of ‘their’ species and habitats. Around a river protected area in western Serbia, this has worked out perfectly: The nature conservation NGO ‘Frame of Life’ has launched a citizen science project, which provides a comprehensive database of the biodiversity worth protecting in the river basin in order to expand the existing protected area fivefold and prevent the construction of a dam.

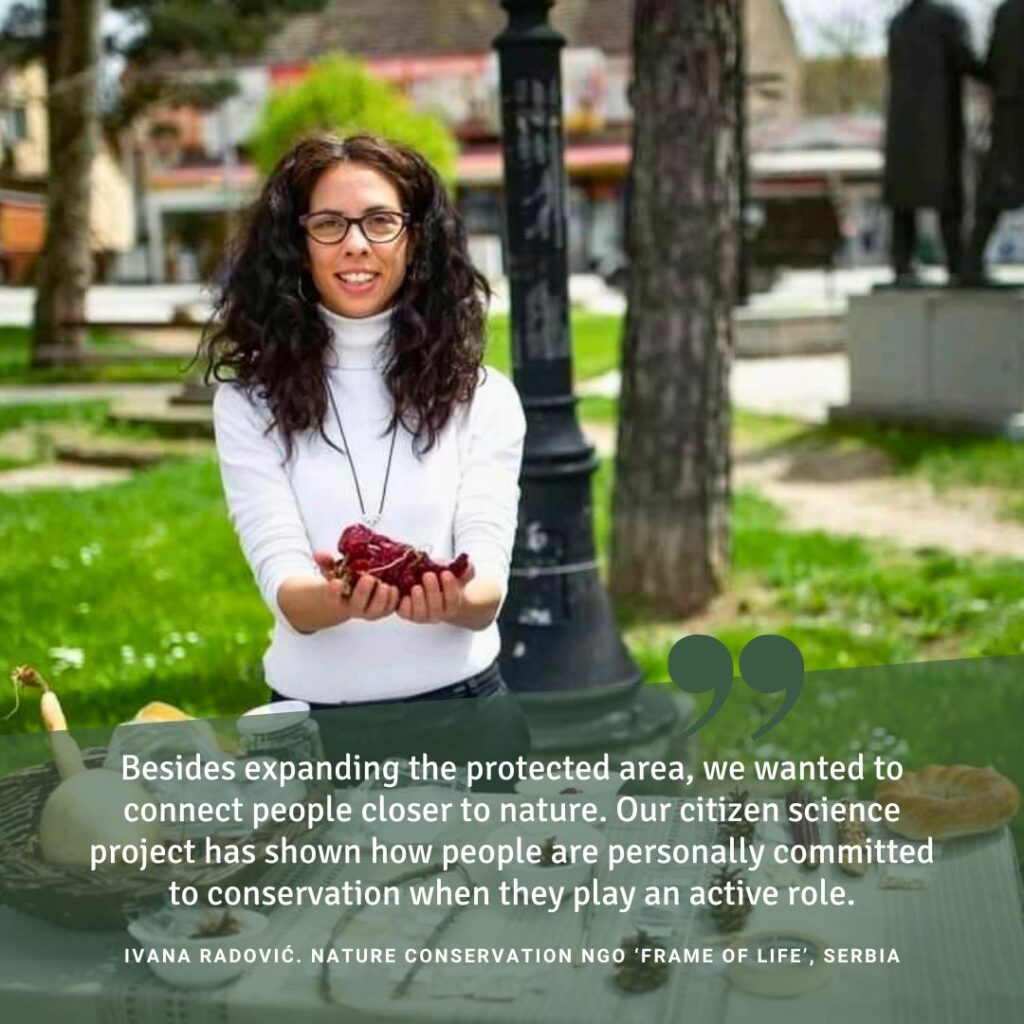

Ivana Radović, a PhD in agriculture at the University of Belgrade, founded the NGO Ecological movement ‘Frame of Life’ with experts from agriculture and biology to promote agrobiodiversity and nature conservation. This NGO has received a Citizen Science grant from the EU-funded Impetus project with their project ‘CITIZENS for SDG15.1’ to provide data-based recommendations for the need to expand the protected area of the “Monument of Nature Ribnica” ecosystem. In our interview, Ivana explains how the project not only contributed to SDG 15.1, which aims to conserve and restore terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems under the heading ‘Life on Land’ (SDG 15). It is also still helping to reconnect people in the region with nature.

How did the Citizen Science project come about?

We came up with the idea of working in this area because Serbia has a very low percentage of protected areas, only about 8 per cent. Compared to the European Union average, which is 25 percent according to the European Environment Agency, this is very low. So we thought about how we could overcome this lack of financial and human resources in order to expand protected areas. And we found that citizen science is a very useful tool to get a large amount of data in a very short time.

“The protected area is very small and the most valuable parts of the river gorge are not protected. Our citizen science project resulted in a comprehensive database to promote the expansion of the protected area and prevent the realization of plans for a 42-meter high dam.”

Another reason why we chose this particular protected area is that it is very small: 28 hectares. However, we have found various documents and data from experts that prove that this area should be protected on a much larger scale. The most beautiful part of the river gorge is upstream and is not protected. It is exposed to pollution and threatened by the planned construction of a 42 metre high dam. So we had the local context of why this valuable part of the river basin should be protected and the national context of the low percentage of protected areas.

How did you involve the population and who took part?

We launched a public appeal via various media channels. This was very important because it allowed a large number of people with different educational backgrounds, different ages, etc. to apply. We made a selection of 29 citizen scientists, from children to older people, lawyers, artists, craftspeople, in other words people who do not come from the field of science. But we also brought in 13 experts from the Faculty of Biology at the University of Belgrade to support the citizen scientists in their adventure. All citizens were active in two areas: Desk research and field research. The desk research was conducted using literature data on the geological heritage and biodiversity in the area. The field research involved day and night work due to the different groups of organisms. This fieldwork was carried out in the gorge upstream to cover the unprotected area. Experts teamed up with citizen scientists who could use publicly available mobile apps, e.g. for bird identification, or books to find out what they found in the field.

Which were the main challenges while implementing the project?

We faced the challenge of getting people of different ages and educational backgrounds to use scientific vocabulary. We also had to be aware of limitations, such as the accessibility of some of the caves we were investigating. This meant that not everyone was able to participate fully in the fieldwork. Another challenge is the quality of the data collected. This is why the help of experts was so important, as they helped us to validate the data. They were able to validate 98 per cent of the data, which then went to the state Institute for Nature Conservation, which is responsible for protected areas in Serbia. We saw that, with enough time and help from experts, every initiative in Europe can overcome these challenges.

What other goals did you pursue with the Citizen Science project?

In addition to expanding the protected area, we also wanted to connect people more closely with nature. Our research has shown that people get personally involved in nature conservation when they play an active role. It is much more difficult to involve them if they are just visitors. Another point is to connect people with science. Natural sciences in particular are considered difficult, and biology is a wonderful field in which you can even become an expert as a citizen scientist. Many good biologists have been citizen scientists.

“Our findings of a total of 944 species, 6 of which are completely new to science and 12 new to Serbia, show the great importance of this ecosystem on a European scale. We therefore call on the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) to reconsider plans for possible financing of a dam on the Ribnica River.”

What did the citizen scientists find out?

We have found a total of 944 species, of which 6 are completely new to science and 12 are new to Serbia. Among these six species are two species of snails,three species of centipedes and one species of insects. As a final result, we applied to the Institute for Nature Conservation for a five-fold extension of the area compared to the current status, so that the 28 hectares would be extended to the entire upstream part of the area. The complexity of this ecosystem and the species found have shown us that this area is a glacial refugium, which means that during the ice age, species sought refuge in this area. The research results have shown us that this unique ecosystem is of great importance not only on a national, but also on a European and global scale. We therefore call on the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) to reconsider plans for potential funding of a dam on the Ribnica River, due to the possibility of permanent destruction of this beautiful area and its rich biodiversity.

How did you ensure that people didn’t just research species that they sympathise with?

The beauty of our project is that there are many caves in this area with a biodiversity that is particularly vulnerable and fragile, but also very unique. We had very good experts for caves who drew the attention of the citizen scientists to the invisible biodiversity like small invertebrates and convinced them that all biodiversity is important. Of course people like otters or are more interested in bats. But I think we have succeeded in drawing people’s attention to this ecosystem with all its insects like Trichoptera and the many other less visible inhabitants.

Did you observe that participants also developed emotional connections with nature?

Actually, children are the best observers. They see so many details that adults don’t and had fun spotting all kinds of species because they are not afraid of nature – something that is spreading worldwide. But it’s really nice that the adults have stayed in touch with us too. We now have another two-year project at the Faculty of Biology at Belgrade University: in the same area, we are carrying out the assessment of ecosystem services, now based on our findings on this biodiversity. This allows the citizen scientists to continue their work in a different area, and their willingness to continue shows us their commitment to nature in this area. We also provide regular feedback on the two projects in which people are involved, e.g. on the progress made in preventing the planned construction of the dam and the expansion of the protected areas. And this area is also important to the people, because an important monastery is located in the protected area, so cultural heritage also plays a major role.

What are your recommendations for rangers and protected areas that want to integrate citizen science for their conservation and environmental education goals?

Citizen science can be beneficial for both sides: more data is collected, which should not be underestimated as a source for promoting the area to be protected. On the other hand, citizen science gives people a sense of belonging to a natural place and connects them more personally and emotionally to that protected area. Only if people can play an active role will the wider population become truly aware of the global threat to biodiversity. And I think citizen science is really great for making that personal connection and bringing us back to nature. It’s also a really nice hobby and a fun way to spend time in nature.