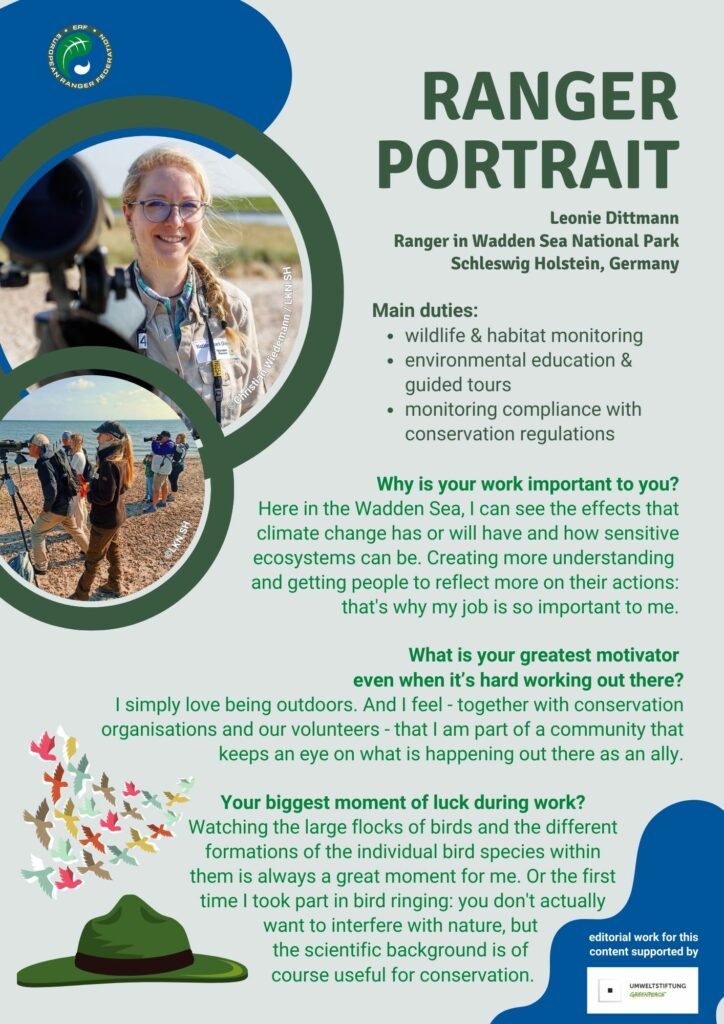

Protecting biodiversity: In the Wadden Sea UNESCO World Heritage Site with around 10,000 animal and plant species, this is a task also of central importance for human future well-being. Leonie Dittmann works in the German Schleswig-Holstein Wadden Sea National Park on the North Sea island of Föhr to do just that. The national park ranger creates understanding for the protection of the Wadden Sea by allowing people to experience the wildlife of the mudflats. We accompanied her.

A large flock of oystercatchers is resting on the road we are travelling along towards the salt marshes, which border the only zero-use zone in the national park. Ranger Leonie Dittmann slowly continues driving – and the sky above us is all black, white and red flapping cloud. Which leads to the topic: human interests and conservation – how do they go together?

In this case, rather symbolically. After all, the animals are not alone on the island. And we are here to keep it that way: Leonie works daily to ensure that wildlife and its habitats remain diverse in this part of the Wadden Sea National Park. For example, by showing them to visitors like me.

Sharing enthusiasm puts nature conservation in people’s hearts

With a few steps, she sets up a scope. ‘Here we have curlews, redshanks, oystercatchers, over there wigeons and barnacle geese,’ she says after looking through the viewfinder. Time and again, flocks flutter up from the mudflats, this time far away from us. At some point even I recognise the long, curved beak of the curlew. There are also lapwings and golden plovers. These are some of the moments, Leonie tells later, that always move her: ‘Watching the large flocks with the different bird species and their formations: It gives me a special feeling.’ A feeling that she is happy to share on her birdwatching tours, bringing nature conservation closer to people’s hearts.

Leonie has to repack the spotting scope for today without us delving further into the wading bird world at Sandhaken, the only beach section on Föhr closed for bird protection all year round. Clouds reflect in the water everywhere on land: The high tide prevents us from going any further. Even the Godel, a natural river with direct connection to the sea, is higher than ever between the meadows of the Godel lowlands, says the ranger. The FFH conservation area with its largely natural transition into the North Sea and its regularly flooded salt marshes is a unique habitat for many specialists that have become rare in the Wadden Sea.

The conservation and land use planning graduate has been a ranger at Schleswig-Holstein Wadden Sea National Park Authority since 2022. Off the German North Sea coast, a total of three national parks protect the Wadden Sea, UNESCO World Heritage Site and the world’s largest contiguous sand-mudflat system. It stretches over 500 kilometres along the coastline of Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands. The island of Föhr, which is Leonie’s area of operation next to the neighbouring island of Amrum, is not part of the national park as such. But the part 150 metres from the dyke, where the Wadden Sea begins, is. And of course the young ranger is also out and about in the other nature areas on the island.

‘Small Five’: key species for the ecology of the Wadden Sea

In addition to guided tours on the unique bird life – the Wadden Sea is the most bird-rich area in Central Europe and a central hub on the East Atlantic migration route of coastal birds – she is involved in monitoring bird species and their habitats: through the simultaneous censuses throughout the national park, ringing to understand the flight routes and the monitoring of the sea fringe, which provides information on the current spread of bird flu from washed-up carcasses, for example. Or about the extent of environmental pollution, for example from paraffin released by ship tankers out at sea.

In addition to ornithological excursions, the ranger is involved in monitoring species and habitats, assessing risks to wildlife from disease or pollution, oversees compliance with regulations, leads Wadden Sea tours, maintains information boards and cooperates with partner organisations and volunteers in many of these areas.

She also oversees compliance with conservation regulations on the island and organises guided tours of the Wadden Sea, explaining to visitors the central role of the ‘Small Five’ lugworm, cockle, shore crab, wadden snail and North Sea shrimp in the coastal ecosystem. She maintains the national park’s information boards and signs and works closely with the islands’ conservation organisations and initiatives in many areas.

Mediating between tourists, residents, leisure activity providers and nature

Meanwhile, we are looking out of the large window front upstairs in a huge barn that has been converted for birdwatching. Once part of a farm, a private owner now provides it to the Elmeere conservation association, one of the Island Ranger’s co-operation partners. The barn is permanently open with its exhibition on birds and nature in the amphibious landscapes between water and land restored by the association. There are also spotting scopes here, through which we now take in the flooded meadows from above: lots of barnacle geese, a few wigeons and redshanks.

The biggest area of conflict, which has not been aggressive so far, is dog owners who do not adhere to the leash requirement. But of course the ranger also has discussions with people who do not agree with decisions made by the national park administration.

The association is at the centre of the conflict between nature use and conservation, says Leonie. The whole spectrum is involved: farmers who cooperate well. But also the opposite, including hostility. Fortunately, her biggest, so far non-aggressive area of conflict is dog owners who do not respect the leash requirement. ‘The direct contact between the national park and agriculture or fishing, where income interests are at stake, goes through the national park administration,’ says Leonie. Of course, she also occasionally has a conversation with someone who disagrees with decisions by the national park administration. ‘But it doesn’t get personal that quickly.’ Her target group is the numerous tourists, residents and providers of leisure activities.

‘Here in the Wadden Sea, I can see the effects that climate change has or will have and how sensitive ecosystems can be. Creating more understanding for this and getting people to think about their actions, for example not letting children climb around in the dunes – that’s the most important part of my job.’ In the way she does her work, the Schleswig-Holstein born is as free as the North Sea wind, which, back outside between the meadows, rattles my rain jacket. ‘There are few predetermined structures, and my predecessor retired quite soon after I joined. So I often decide for myself where to focus my work. In the meantime, I think I fulfil this freedom quite well,’ says Leonie, now in the island’s National Park House.

Wadden Sea hub: 10 to 12 million birds rest here every year on their migration route

Birds are also omnipresent in the National Park House exhibition, of which 10 to 12 million rest in the Schleswig-Holstein Wadden Sea every year. Leonie picks up a stuffed dunlin, which I’m not sure whether I saw it yesterday on the beach or the sanderling. While she introduces a number of other inhabitants of the Wadden Sea, including of course the harbour seal, grey seal and harbour porpoise as marine mammals, I am as enthusiastic about diversity and ranger knowledge as I am doubtful whether I will ever succeed in distinguishing the countless feathered animals with their longer or shorter legs, crooked, straight, short or long beaks.

This was precisely one of the national park ranger’s first steps: ‘I didn’t have much ornithological knowledge until then. So I learnt about all the different bird species here. After my bird tours, I always find it really nice when the participants are enthusiastic about my relatively new knowledge. Or when I have been able to convey new contexts between Wadden Sea, meadow breeders, agriculture and, ultimately, fishing.’ One example is the tern chicks: the warmer water caused by climate change is altering reproduction of the fish, she explains. So they are often already bigger when they arrive in the Wadden Sea – probably too big for the chicks to feed on.

Balancing act: conservation is essential, but residents must make a living

‘However, it’s also important to me not just to provide negative examples: For instance, the population of the rare spoonbill is currently on the rise again – without any significant impact on other birds.’ It is equally important for her to emphasise understanding for legitimate interests on both sides: nature use and conservation. People have to make a living despite, or rather with nature conservation. On the other hand, she says, standing in front of a grey seal specimen, she has to make it clear to all too well-meaning nature lovers: ‘If they have not been weakened by human intervention, it is usually harmful to nurse up such animals and release them back into the wild. Their reproduction would weaken the population.’

Being part of a community that keeps an eye on what is happening out there: This is how the Wadden Sea Ranger sees her position. In the coming season, she says in parting, she wants to concentrate more on the oystercatchers’ breeding clutches. Although the birds can be seen everywhere at the moment, their population has declined sharply across the Wadden Sea. The ground-nesting species is particularly dependent on humans not accidentally trampling the nests. In the case of the ringed plover, Leonie and her community of national park volunteers, conservation organisations and enthusiasts have already achieved a great deal: ‘The locals often mark out the nests for everyone to see from afar.’

editorial work for this

content is supported by