For three cruel years now, the rangers and protected area staff in the protected areas of Ukraine have been working under wartime conditions. How does conservation work under these conditions, how do rangers and how does nature cope with this extreme situation?

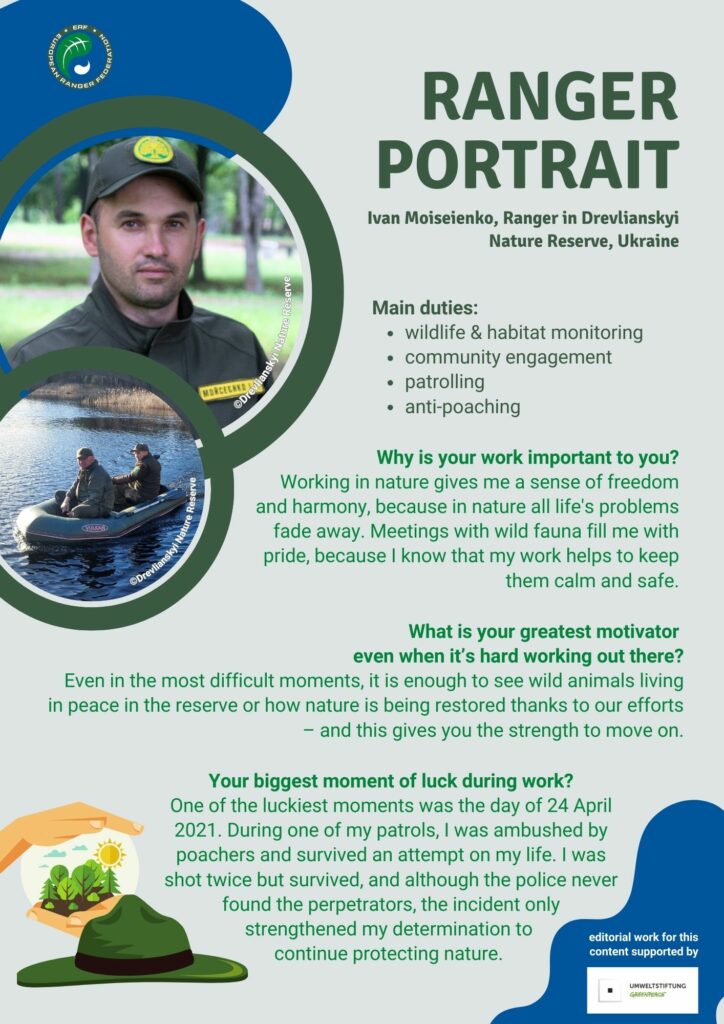

With the help of Maria Gurscaia‘s translation, we spoke to Nataliia Bohdan, co-project manager “Nature Fund of Ukraine” and coordinator of Tellus Conservation’s support for Ukrainian protected areas (see interview), and Ivan Moiseienko, Head of Conservation and ranger in the Drevlianskyi Nature Reserve between Kyiv and Belarus, partly occupied at the beginning of the war. So much for now: the support from the European ranger and conservation community, the feeling of not being alone, is one of the most important things we can all give.

How is the war affecting the working conditions in your protected area?

Ivan: All our employees work under a constant feeling of insecurity. When the full scale invasion started in 2022, the Russian army advanced right through our reserve to Kyiv. From here they tried to occupy Kyiv and bombed the city. As a result, there are still many unexploded ordnance in our area. A lot of work and financial resources are needed to detect and defuse them.

In addition, there is still a risk of special forces entering our districts on the orders of the Russian army. Just six months ago, for example, we noticed exploratory troops in our reserve, probably from Belarus, which borders our region. Additionally, in the beginning of the war, one of our departments was unable to work for months because it was located directly on the border with the invaded Kyiv district. This meant that 2,000 hectares of forest could not be monitored and protected. To this day, my colleagues and I cannot use much of the infrastructure in the nature reserve, only roads that have been checked for dangers such as unexploded mines.

Nataliia: The working conditions depend on the region of Ukraine in which the protected area is located. There are areas that are or were occupied and have many mines in the ground, such as the Drevlianskyi Nature Reserve. But we also have nature reserves and national parks that can operate as usual. In general, we now have a big problem with human resources, as many employees are in the Ukrainian army.

What is the most important role that rangers and park staff currently play for society?

Ivan: We work closely with the Ukrainian army, primarily for the exchange of information. But the army can also benefit greatly from our extensive knowledge of the territory in this important area between Kyiv and the Belarusian border. This has enabled us under occupation to show the soldiers hidden routes to keep them safe.

‘The rangers also help to defuse unexploded ordnance, just as they used their boats to bridge a river for the locals when its bridge was destroyed.’

The rangers also help to monitor the area and defuse unexploded ordnance. Of course, this also protects the civilian population. In the middle of our nature reserve there is also a river whose bridge, the only connection between two regions, was destroyed in the first months of the war. Every day for four months, rangers helped to bring food and other essentials across by motorboat for the isolated population, but also vice versa for people who needed to visit the district town or be taken to hospital as the wounded, for example.

What are the biggest challenges for park staff and rangers on a personal level – how do they deal with the extremely demanding situation?

Ivan: We really have got used to it, because the war has been going on for quite a long time now. We are mainly worried about the people on the front line who are in deadly danger every day.

Nataliia: In the first few months, all the protected areas have tried to help the people and also their colleagues. I am very proud of the staff of these parks and reserves, because all the directors tried to support each other as much as possible. The national park in the Carpathian region, for example, tried to take in people who had moved from the regions affected by the war. And the mutual help was so intense that when one director said they needed fuel for evacuations, another park director and the staff immediately researched how they could deliver this fuel. So it was really a tight network of all the protected areas.

What kind of support could improve the situation for nature conservation work as well as for rangers and park staff at the moment?

Ivan: We are actually already receiving help from Ukrainian NGOs that receive funding from abroad, from international NGOs such as Tellus Conservation, the Frankfurt Zoological Society and other institutions. Recently, thanks to this help, we were able to repair a fire engine. Soon we will probably receive specialised fire-fighting equipment. We are also often supplied with fuel. Tellus Conservation is also thinking about providing us with uniforms to identify us as rangers and park staff. This is necessary for security reasons so as not to be confused with the military. But it is also important to show the public that we are out in the field protecting nature and that we have police rights to do so.

Are there species and habitats that are particularly affected by the war?

Ivan: At the beginning of the war, more than 2,000 hectares of the Drevlianskyi Nature Reserve were damaged by bombs and the fires caused by the explosions. But the good news is that we recently applied, together with the Polytechnic University of Zhitomir, for an EU Life project for the ecological restoration of this area. And indeed, the fauna has recovered very well at the moment. After the occupation, the species returned to our reserve. Some of the populations have even increased, partly due to the curfew, after which people are no longer allowed to be outdoors. In addition, hunting is prohibited in times of war, especially in our border region. The result is that we now have more lynx than before.

Nataliia: The state of nature, in turn, depends very much on the part of Ukraine where the protected areas are located. For example Holy Mountains National Nature Park is very close to the battle line. The whole area in the Donetsk region is mined and suffers from a lot of fires. We don’t know if the area can ever be restored. What we do know is that for some national parks that are now in the line of fire, there is a great risk that they will be irrevocably destroyed.

What will be the greatest challenges for nature conservation work when the war is over?

Ivan: The biggest challenge will be to examine the area and remove the unexploded mines. We have had at least two fatalities, such as forest officials dying because of this. That is why this clearance is priority A. We are also preparing for firefighting in the coming years, as explosive mines can cause forest fires. And as parts of our nature reserve are located in the area affected by the Chernobyl accident, we need to check the current radioactive contamination.

‘Our park must be open to all those who have served in the military and need psychological rehabilitation. But at the moment, such state programmes are not yet well developed.’

This is because many people who have fled the war in Ukraine and want to return will initially not be able to return to their war-damaged or possibly still occupied home regions. In our reserve region, there are many abandoned villages due to the war and radioactive contamination, so we would have room for returnees. And finally, our park must be open to all those who have served in the military and need psychological rehabilitation. There are already such cases, because people here love nature. But at the moment, state rehabilitation programmes for former military personnel are not yet well developed.

Nataliia: As a huge area of protected areas is now occupied or destroyed, we will need much, much support for restoration after the war. Yesterday I spoke to the staff of the Kamianska Sich National Park in the Kherson region, very close to the battle line and occupation area. There are a lot of unexploded mines here, all the administrative buildings have been destroyed.

‘Kamianska Sich National Park in Kherson is in operation. But the employees do everything themselves, always at great risk to their lives because of the mines.’

The park is in operation, but the employees do everything themselves, always at great risk to their lives because of the mines. I think that after the war we will have to think about such protected areas first. Also because the Russians built many trenches here. These fortifications are not only a great risk for people, but also for animals that can’t free themselves if they fall in.

Your greatest wish for the European ranger community: how could rangers best support Ukrainian colleagues?

Ivan: We could of course need training and knowledge on topics that our European colleagues might have a lot of experience with in order to adapt to the new requirements after the war. Equipment could also be needed. Above all, however, we would very much welcome general support. There currently is a discussion about depriving the state protection service of its powers in favour of the state environmental inspection. In practice, this will not yield positive results, as the State Environmental Inspectorate will not always be able to respond promptly to violations of environmental legislation. So we also need this support to show that we are doing our job in cooperation with current partners against environmental crimes as we did during the war and will do so to the best of our ability under all circumstances.

Nataliia: We have spoken to ten national parks and nature reserves about training and have already introduced the Spatial Monitoring and Reporting Tool (SMART) as a digital tool. Since we cannot help all of the more than 50 national parks in Ukraine, it would be very nice to find ways in which all protected areas in Ukraine could use SMART and receive further support, for example training on fire management and combating poaching. Above all, however, it is very important for all of us who work in and with protected areas to know that we are not alone in the European community.

На війні і попри війну: як українські рейнджери працюють для природи

Вже три жорстокі роки ,працівники природно-заповідних територій України працюють в умовах воєнного часу. Як працює природоохоронна діяльність у цих умовах, як працюють рейнджери та як природа справляється з цією екстремальною ситуацією?

Про це ми поговорили з Наталією Богдан, менеджером проєктів БО «Фонд природи України» та координатором підтримки природоохоронних територій України від Tellus Conservation (див. інтерв’ю), та Іваном Мойсієнком, начальником відділу охорони ,Древлянського природного заповідника між Києвом та Білоруссю, який був частково окупований на початку війни.

Наразі: підтримка європейської спільноти рейнджерів та природоохоронців, відчуття того, що ми не самотні, є однією з найважливіших речей, які ми всі можемо дати.

Як війна впливає на умови праці на вашій заповідній території?

Іван: Усі наші працівники працюють у постійному відчутті небезпеки. Коли почалося повномасштабне вторгнення у 2022 році, російська армія просунулася прямо через наш заповідник до Києва. Звідси вони намагалися окупувати Київ і бомбили місто. Як наслідок, на нашій території досі є багато боєприпасів, що не розірвалися. Щоб їх виявити та знешкодити, потрібно багато роботи та фінансових ресурсів. Крім того, все ще існує ризик введення в наші райони спецпідрозділів за наказом російської армії. Лише півроку тому, наприклад, ми помітили розвідувальні війська в нашомузаповіднику, ймовірно, з Білорусі, яка межує з нашим регіоном. Крім того, на початку війни одне з наших відділень не могло працювати місяцями, оскільки знаходилося безпосередньо на кордоні з окупованим Київським районом. Це означало, що 2000 гектарів лісу не могли контролюватися та охоронятися. До сьогодні ми з колегами не можемо користуватися більшою частиною інфраструктури заповідника, лише дорогами, які були перевірені на наявність небезпек, таких як міни, що не розірвалися.

Наталя: Умови роботи залежать від регіону України, в якому знаходиться заповідна територія. Є території, які окуповані або були окуповані і мають багато мін у землі, як, наприклад, Древлянський природний заповідник. Але у нас також є заповідники та національні парки, які можуть працювати у звичайному режимі. Загалом, у нас зараз велика проблема з людськими ресурсами, оскільки багато працівників перебувають в українській армії.

Яку найважливішу роль зараз відіграють рейнджери та працівники парків для суспільства?

Іван: Ми тісно співпрацюємо з українською армією, в першу чергу для обміну інформацією. Але армія також може отримати велику користь від наших глибоких знань про територію в цій важливій області між Києвом і білоруським кордоном. Це дозволило нам в умовах окупації показати військовим приховані маршрути, щоб забезпечити їхню безпеку. Працівники служби державної охорони також допомагають моніторити територію та знешкоджувати боєприпаси, що не розірвалися. Звичайно, це також захищає цивільне населення. Посеред нашого заповідника протікає річка, міст через яку, єдиний зв’язок між двома регіонами, був зруйнований у перші місяці війни. Щодня протягом чотирьох місяців працівники служби державної охорони допомагали переправляти їжу та інші предмети першої необхідності на моторних човнах для ізольованого населення, а також навпаки – для людей, яким потрібно було відвідати районне місто або, наприклад, доставити поранених до лікарні.

Які найбільші виклики постають перед працівниками парку та рейнджерамина особистому рівні – як вони справляються з надзвичайно складною ситуацією?

Іван: Ми вже звикли до цього, адже війна триває вже досить довго. Найбільше ми переживаємо за людей на передовій, які щодня наражаються на смертельну небезпеку.

Наталя: У перші кілька місяців усі природоохоронні території намагалися допомагати людям, а також своїм колегам. Я дуже пишаюся персоналом цих парків і заповідників, тому що всі директори намагалися максимально підтримувати один одного. Наприклад, національний парк у Карпатському регіоні намагався прийняти людей, які виїхали з регіонів, що постраждали від війни. Взаємодопомога була настільки інтенсивною, що коли один директор говорив, що їм потрібне пальне для евакуації, інший директор парку разом з персоналом негайно досліджував, як можна доставити це пальне.. Тож це була справді тісна мережа всіх природоохоронних територій.

Яка підтримка могла б покращити ситуацію для природоохоронної роботи, а також для рейнджерів та працівників парків на даний момент?

Іван: Насправді ми вже отримуємо допомогу від українських громадських організацій, які отримують фінансування з-за кордону, від міжнародних організацій, таких як Tellus Conservation, Франкфуртське зоологічне товариство та інших установ. Нещодавно завдяки цій допомозі ми змогли відремонтувати пожежну машину. Незабаром ми, ймовірно, отримаємо спеціалізоване протипожежне обладнання. Також нам часто допомагають з пальним. Tellus Conservation також думає про те, щоб забезпечити нас уніформою, щоб ми могли ідентифікувати себе як працівників служби державної охорони і працівників парку. Це необхідно з міркувань безпеки, щоб нас не сплутали з військовими. Але також важливо показати громадськості, що ми працюємо в полі, захищаючи природу, і що у нас є, повноваження для цього.

Чи існують види та оселища, які особливо постраждали від війни?

Іван: На початку війни понад 2 000 гектарів Древлянського природного заповідника було пошкоджено бомбами та пожежами, спричиненими вибухами. Але хороша новина полягає в тому, що нещодавно ми разом з Житомирським політехнічним університетом подали заявку на проект EU Life для екологічного відновлення цієї території. І дійсно, на даний момент фауна дуже добре відновилася. Після окупації види повернулися до нашого заповідника. Деякі популяції навіть збільшилися, частково завдяки комендантській годині, після якої людям більше не дозволяється перебувати на відкритому повітрі. Крім того, полювання заборонено під час війни, особливо в нашому прикордонному регіоні. В результаті ми маємо зараз більше рисей, ніж раніше.

Наталя: Стан природи, в свою чергу, дуже залежить від того, в якій частині України розташовані заповідні території. Наприклад, Національний природний парк «Святі гори» знаходиться дуже близько до лінії бойових дій. Вся територія в Донецькій області замінована і страждає від великої кількості лісових пожеж. Ми не знаємо, чи зможемо ми коли-небудь відновити цю територію. Що ми точно знаємо, так це те, що для деяких національних парків, які зараз знаходяться на лінії вогню, існує великий ризик того, що вони будуть безповоротно знищені.

Якими будуть найбільші виклики для природоохоронної діяльності після закінчення війни?

Іван: Найбільшим викликом буде обстежити територію і вилучити міни, що не розірвалися. У нас було щонайменше два смертельних випадки, коли через це гинули працівники лісової охорони. Саме тому це очищення є пріоритетом . Ми також готуємося до пожежогасіння в найближчі роки, оскільки вибухові міни можуть спричинити лісові пожежі. А оскільки частина нашого природного заповідника знаходиться на території, що постраждала від аварії на Чорнобильській АЕС, нам потрібно перевірити поточний рівень радіоактивного забруднення. Це пов’язано з тим, що багато людей, які втекли від війни в Україні і хочуть повернутися, спочатку не зможуть повернутися в свої пошкоджені війною або, можливо, все ще окуповані рідні регіони. У нашому регіоні є багато покинутих сіл через війну і радіоактивне забруднення, тому у нас буде місце. І, нарешті, наш заповідник має бути відкритим для всіх тих, хто служив у війську і потребує психологічної реабілітації. Такі випадки вже є, адже люди тут люблять природу. Але наразі державні програми реабілітації для колишніх військових ще недостатньо розвинені.

Наталя: Оскільки величезна територія природно-заповідних територій зараз окупована або зруйнована, нам знадобиться дуже і дуже велика підтримка для їх відновлення після війни. Вчора я розмовляла з працівниками Національного парку «Камінська Січ» у Херсонській області, який знаходиться дуже близько до лінії фронту та зони окупації. Тут багато нерозірваних мін, всі адміністративні будівлі зруйновані. Парк працює, але працівники все роблять самі, завжди з великим ризиком для життя через міни. Я думаю, що після війни ми повинні будемо думати про такі території в першу чергу. Ще й тому, що росіяни побудували тут багато окопів. Ці укріплення є великим ризиком для тварин, які не можуть вибратися, якщо потраплять в них.

Ваше найбільше побажання європейській спільноті рейнджерів: як рейнджери можуть найкраще підтримати українських колег?

Іван: Звичайно, нам може знадобитися навчання і знання з тих тем, в яких наші європейські колеги можуть мати великий досвід, щоб адаптуватися до нових вимог після війни. Також може знадобитися обладнання. Наразі обговорюється питання про позбавлення державної служби охорони її повноважень на користь державної екологічної інспекції. На практиці це не дасть позитивних результатів, оскільки Держекоінспекція не завжди зможе оперативно реагувати на порушення екологічного законодавства. Тому нам також потрібна ця підтримка, щоб показати, що ми виконуємо свою роботу у співпраці з нинішніми партнерами по боротьбі з екологічними злочинами, як ми це робили під час війни, і будемо робити це якнайкраще за будь-яких обставин.

Наталя: Ми поговорили з десятьма національними парками та заповідниками про навчання. Ми вже запровадили Інструмент просторового моніторингу та звітності (SMART) як цифровий інструмент. І оскільки ми не можемо допомогти всім більш ніж 50 національним паркам в Україні, було б дуже добре знайти способи, як усі природоохоронні території в Україні могли б використовувати SMART і отримати подальшу підтримку, наприклад, тренінги з управління пожежами та боротьби з браконьєрством. Однак, перш за все, для всіх нас, хто працює на природоохоронних територіях, дуже важливо знати, що ми не самотні в європейському співтоваристві.

editorial work for this

content is supported by