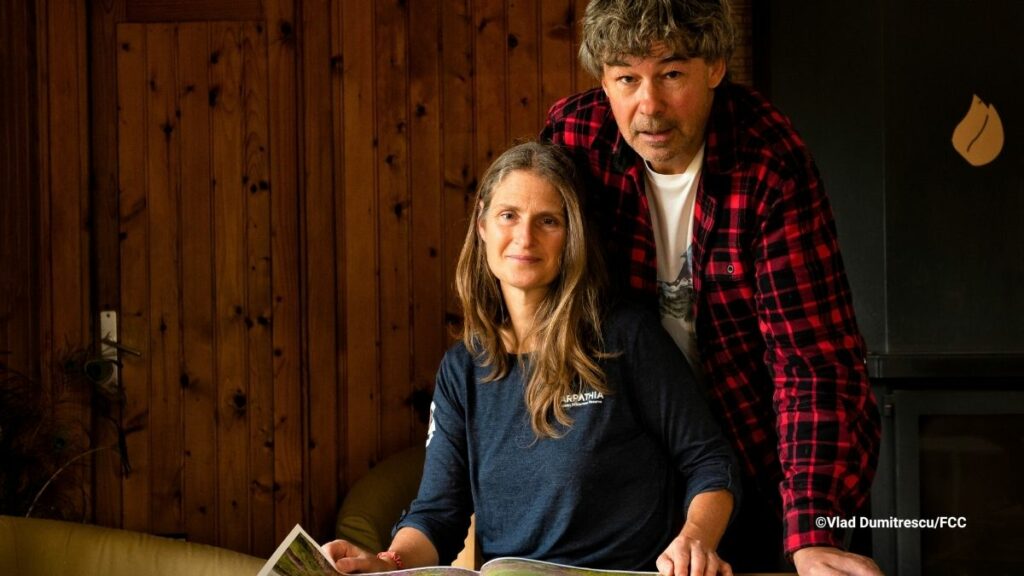

Just watch: Wildlife biologists Barbara and Christoph Promberger couldn’t do that. Originally following the wolves roaming the Romanian Carpathians, the massive deforestation in the 2000s shocked the couple so much that they began to mobilise funds around the world. To this day, their aim is to buy up the forest areas and place them under full protection – until Europe’s largest national park is created on around 250,000 hectares around the Făgăraș Mountains.

The work of the Foundation Conservation Carpathia (FCC), founded by the Prombergers, is the first initiative to establish a national park in Europe by private investors. Last year, it earned the couple the most important German media award Bambi for outstanding commitment to climate and nature conservation. We spoke to Barbara and Christoph about the aims and milestones of their pioneering work to date. Their approach to integrate the needs of the population fits the focus of the European Ranger Congress in October 2025, which we will be organising in partnership with the FCC and the Romanian Ranger Association in the immediate vicinity of the planned national park. Read here about the ways how the local population benefits from the foundation’s goals and how important the work of rangers is for those.

Your aim is to create a kind of Yellowstone in Romania, the largest national park in Europe. What was the background to the idea?

Christoph: This is a conclusion from the fact that we have a forest area of more than 200,000 hectares here, which is unfragmented, still has the entire mammal fauna including bears, wolves and lynxes, and where there are still large areas of primeval forest. From a European and national perspective, the question is how it can be that this area is not yet a national park. And because it is such a large area, it could be a truly iconic national park in Europe. There are many national parks in Europe, but none stand out like Yellowstone National Park in the USA or Kruger National Park in South Africa.

Where do you stand with this goal, and what still needs to be done?

Barbara: National parks are a government decision. And in Romania, this can only be made if the affected communities agree. As a private initiative, we have already purchased 28,000 hectares of forest through our foundation, a large proportion of the private forests that we have placed under full protection. The rest of the forests are owned by landowner co-operatives or are municipal and state forests. We have to convince all these owners and the communities in the region that a national park is economically better than utilising these forests.

“In the first phase, we purchased land for conservation and renaturalisation. Now we started working with the communities and strengthening the socio-economy in the surrounding area.“

In the first phase, we focussed on purchasing land in order to carry out the first conservation measures and to renaturalise areas that had already been cleared by replanting. We also reintroduced wild animals that no longer existed here, such as the European bison or beavers, which had disappeared on the southern side. In the next step, we want to bring back the vultures, which would pretty much complete the ecosystem. Now, in the second phase, we have started to work with the communities and strengthen the socio-economy in the areas surrounding the planned national park.

What challenges do you face in this endeavour to convince people?

Christoph: They are the same as those we see throughout Europe when it comes to establishing protected areas. People are afraid of restrictions or interference with their private property. There is also the fear that the supply of firewood may no longer be guaranteed. And many of those who currently control forestry are spreading diffuse fears of ‘someone coming from abroad who wants to take it all away from us and nationalise it again’. This gets through to people, especially if they don’t understand exactly what is at stake and don’t have the experience of how much good a national park can do. We need thousands of one-to-one conversations in which we take people’s fears seriously, offer answers and take them to areas of existing national parks to see how well the local population gets on with it.

“It may take years to convince every single one in the about 24 communities around the planned national park. However, many already see the national park as a good option.”

That sounds like a lot of work and time: who is doing this work and what time horizon do you anticipate?

Barbara: We now have 150 employees, the majority of whom come from the communities and thus are important local ambassadors for us. This allows people to see that it is not the foreigners trying to take the land from them, but that the locals are standing up for the national park. This support must stem from the bottom up so that the national park can be created out of conviction instead of pressure – the only way it can be maintained sustainably over such a large area. In the beginning, we had to deal with a lot of prejudice and organisations that denounced our project. As a result, we had no access to some communities for a long time. These blockades are only now being overcome. We do a lot of environmental education in schools, which is incredibly well received. In many communities, this is what gives us access in the first place. It may take years to convince every single one in the about 24 communities around the planned national park. However, in places where we have already bought forests, many communities already see the national park as a good option.

How can people in the national park area make a living?

Christoph: Tourism is a key factor. And those who live from tourism are automatically against logging, so we gain more allies. We combine this tourism with food production, which promotes the small-scale farming structure that is still very much in evidence here in the mountains. We help with branding, licences, marketing and sales. Tourism is also good for them, and by recognising that it is created by protecting the forests, we gain further support. We also promote the development of infrastructure, support sports clubs and events in order to gain broad acceptance.

How do you manage to provide this support – and how equivalent is the income that people earn from this to that generated by logging, for example?

Barbara: Only a handful of people benefit from forestry, many of whom made money illegally from logging when the forests had to be returned to the population in the 2000s after the Ceaucescu regime’s expropriation. Most people from the communities have nothing to gain from this except the clear-cut areas and the resulting problems, such as erosion. For this large majority, the conversion to a conservation-friendly economy is a real advantage. But it simply takes time to establish certain standards in tourism, for example, where there was hardly any tourism before. Accordingly, it needs time for people to realise income benefits. We ourselves have financed ourselves from the outset with a mixture of public and private funds, with increasing sponsorship from Romanian companies. The fact that they offer not only money but also access to their employees helps us to publicise our project nationwide.

“Only a handful of people benefit from forestry. For the large majority, the conversion to a conservation-friendly economy is a real advantage. But it takes time to establish certain standards in tourism, for example.”

More wilderness also means more wild animals. How do you manage human-wildlife conflicts?

Christoph: There are increasingly frequent encounters between bears and humans due to various complex reasons such as climate change, land use or human waste disposal practices and other aspects that are independent of the national park. We have several rapid response teams that deal in particular with conflicts between grazing animals and bears. In an emergency, livestock owners can call on the rangers, who are equipped with rubber bullets, infrared drones and other equipment. The rangers initially chase the bear away and try to relocate it. In the end, they may even shoot it.

Barbara: We have leased several hunting areas and founded a hunting association to obtain hunting licences. This allows us to manage an area of 78,000 hectares for hunting purposes, exclusively for conflict management. So if bears cause problems in the villages, we can act together with a local commission. This is viewed very favourably by the people.

What role do rangers generally play in your organisation?

Christoph: We certainly have more than 50 per cent rangers among our employees in very different roles. In addition to wildlife conflict management, we have rangers in wildlife monitoring. Other rangers work in the reintroduction projects for bison and beavers, hopefully soon also vultures, and many rangers ensure the protection of the 28,000 hectares of forest that we have purchased. All rangers come from the villages and bring our message to the communities through their families, neighbours and friends.

There is certainly centuries-old knowledge about nature in these communities. Do you utilise this knowledge, traditions in dealing with nature and the local culture beyond the employment of local people?

Barbara: When it comes to livestock farming, the local population is way ahead of those in the Alps, for example. The animals here have never been kept unguarded in the mountains, but always in a functioning system with guard dogs and shepherds.

“There is none of the hatred of wolves or bears among the farmers here that we see elsewhere.”

That is why there is none of the hatred of wolves or bears that we see elsewhere. To maintain this, we work together with shepherds and have a livestock guarding dog programme in which we breed the Carpatin, among others, as a human-compatible dog that specialises in protection against large predators. However, we see that this form of livestock farming is declining because fewer and fewer people want to spend the summer with the animals in the mountains. So we expect conflicts to increase. With the support of shepherds and the livestock guarding dog programme, we are trying to counteract this.

In your experience, what is most important for the establishment of new protected areas to be a success – and what would you do differently today?

Barbara: One thing we have certainly learnt is that communication is extremely important. We started thinking about this too late. We knew that we were doing something that was positive and right, but we didn’t analyse the fact that others saw it differently. Before we had even communicated our actual vision, the opponents of our project took over and put it in the wrong light. We have since organised our communication. But we are still dealing with the long-term consequences today.

Christoph: In general, a concept for financing protected areas in the current situation of tight budgets and low priority for nature conservation will certainly be met with great openness by governments. And in areas like Central Europe, developing concepts with the local communities that take their interests into account is the ultimate. Because a national park against the local population: that will never work.