Environmental education – clearly, these are visitor tours, lectures and the like, which are part of many rangers’ tasks. Not so clear to many European rangers is what the concept of nature and heritage interpretation is all about. We spoke to Thorsten Ludwig and Urs Wegmann: two who not only explain interpretation, but also that it is actually the rangers‘ very own language and can enormously advance their work also in supervisory tasks. Because the aim is to convey natural phenomena in a way that touches people’s hearts and awakens responsibility for their protection.

Thorsten is a professional interpreter: after studying archaeology and working in a national park, he has a master’s degree in interpretation, is an independent interpretation trainer and planner and was managing director of Interpret Europe, the European Association for Heritage Interpretation, from 2015 to 2021. Urs, our former ERF President, is heavily involved in the development and training of the ranger profession in Switzerland. However, he only learnt about interpretive rangers at the US World Ranger Congress in 2016. How this led him to the Certified Interpretive Guide (CIG), to what extent the interpretive approach originates from rangers and how poorly knowledge of it is spread among Europe’s rangers: Urs and Thorsten talk about this in this interview.

What exactly is Nature Interpretation?

Thorsten: Interpretation means interpreting something and giving it a meaning. The term actually goes back to John Muir, who is regarded as the founding father of nature conservation in the USA. In 1871, he wrote in his notebook in what would later become Yosemite National Park: ‘I’ll interpret the rocks, learn the language of flood, storm and the avalanche. I’ll acquaint myself with the glaciers and wild gardens, and get as near the heart of the world as I can.’ The US National Park Service refers to this quote time and again. It shows that interpretation is an individual process to give things meaning. What is special about nature interpretation in protected areas is that it combines this personal process with facts. According to the founder of nature and culture interpretation, the journalist Freeman Tilden, this is an art whose skills can be learnt. It is about going beyond the mere explanation of factual contexts to a mediation between people and things; a mediation that touches people’s hearts.

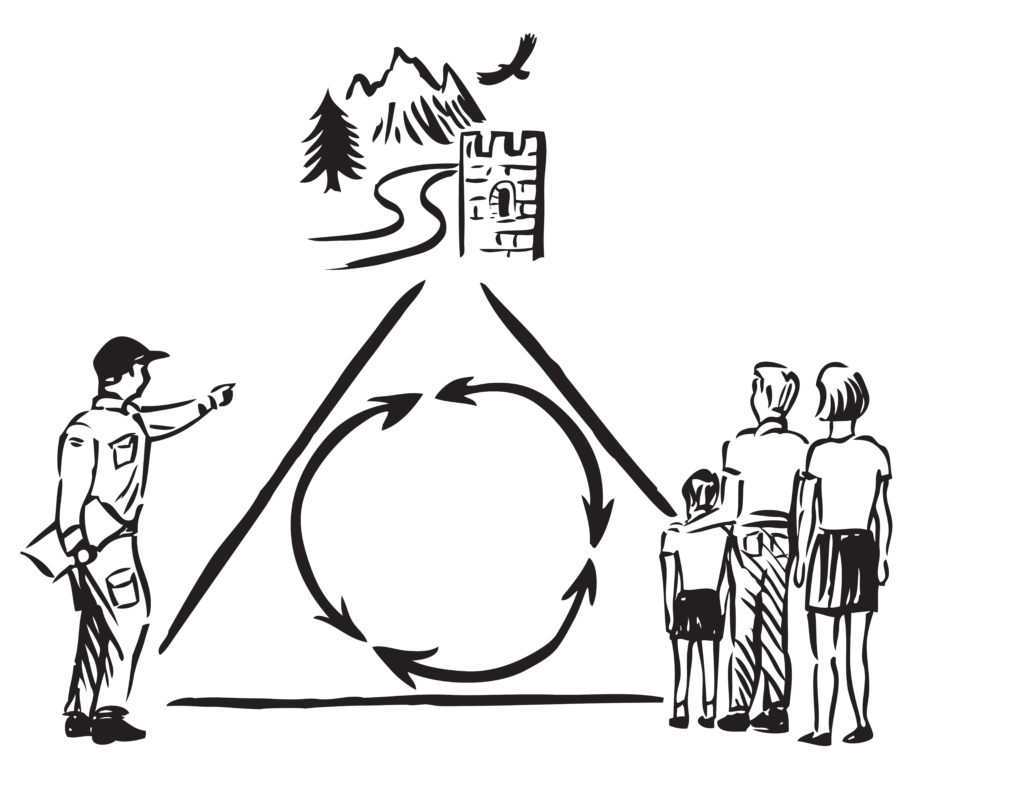

Urs: That was also the big aha effect for me, which I try to explain to rangers that I teach myself with the interpretive triangle. It’s all about relationships: Firstly, the interpreter, in our case the ranger, needs a relationship with the natural phenomenon or object. What I really like is that he should also establish a relationship with the visitor through open questions and other techniques. Because it’s easy for a ranger to get into lecturing. But once the interpreter has established these two relationships, he or she can help the visitor to strengthen the relationship with the natural phenomenon.

What skills should a ranger have to be a good interpreter?

Thorsten: A great advantage that rangers have – and interpretation comes from rangers – is that a ranger works on the ground in the things or natural phenomenons at stake. Making these things tangible is a very important skill. For us, this has five aspects: The visitor has a first-hand experience, thinks about it and draws conclusions from it, is moved by it, comes to deeper insights and finally has the opportunity to discuss this with others. This is a single process in which the interpreter always starts with the experience. This is at the top of the interpretive triangle mentioned by Urs: What is there on site that particularly appeals to people? Then it’s about creating resonance and participation, the second part of the interpretive triangle. The aim is to bring the two together, based on an attitude of responsibility for the natural and cultural heritage as the third component of the interpretive triangle: How can I strengthen it and also recognise that other people may have a different understanding and a different heritage? The centre of the triangle is ultimately about offering pathways to deeper meaning. So I have to bring together the three components, in this case the natural phenomenon, the visitors and the ranger, in one strong idea.

“A great advantage that rangers have is that they work on site in the things or natural phenomenons at stake. Making these things tangible for visitors is a very important skill.”

Thorsten Ludwig, Interpretation trainer and planner ©MIK

How did the method of interpretation come about?

Thorsten: Freeman Tilden first established the principles in the 1950s by watching rangers at work in American national parks and writing down the interesting aspects. This resulted in his book ‘Interpreting Our Heritage’, commissioned by the US National Park Service. It contains principles such as that I shouldn’t do anything that has nothing to do with people’s lives. This is in line with the way journalists work, always keeping in mind that people should want to read their articles. But of course I also want to pass on facts. Following the interpretation approach, I first identify which of these facts or related objects common people can relate to. For us at Interpret Europe, two terms are at the centre of this: meaningful and mindful, so that things become meaningful to people and that they develop mindfulness towards other people and ultimately the planet.

“Traditional ranger tasks such as supervision require very similar skills as for nature interpretation. The ability to create resonance in others is just as important here.”

Urs Wegmann, Swiss ranger and Certified Interpretive Guide ©Stefan Walter

What is the specific significance of nature interpretation for ranger work?

Urs: Traditional ranger tasks such as supervision also require very similar skills as for nature interpretation. After all, educational and supervisory tasks are not the opposing poles that they are still perceived to be in many places. The ability to create resonance with others is also important for rangers who see themselves more as police officers. If I can help a visitor who might misbehave to establish a relationship with the nature of the protected area and thus develop responsibility for its protection, this must be an integral part of ranger work as a whole – and not just of guided tours for visitors.

How does the Interpret Europe network work and how are rangers involved?

Thorsten: Our aim is to contribute to sustainable development in society. UNESCO has developed recommendations for value-based heritage interpretation, which all centres in UNESCO World Heritage Sites, biosphere reserves and geoparks should adopt as a matter of principle. As a network, Interpret Europe endeavours to establish links between European stakeholders. Many of our members are rangers, but we are still working on improving the dialogue between them. Last year, Urs Reif, President of the European Ranger Federation, gave a keynote speech at our annual conference, and a delegation of Swiss rangers was present at this year’s conference in Slovenia. But we would like to see the ranger community at Interpret Europe take on a much stronger shape and work more closely with the ERF. We are only at the beginning.

Is this also due to the fact that Nature Interpretation is not widespread in Europe?

Urs: I myself had to travel to the World Ranger Congress in the USA to link Nature Interpretation with the ranger profession. Later, as President of the European Ranger Federation, I realised that the ranger profession in Europe is extremely diverse. In some European countries, the job description of a ranger is strongly focussed on police-like tasks, and some rangers are given police powers. In Europe, we have a divide between rangers who do a lot of environmental education and prevention work and those from countries where they have a strong supervisory role. And I see huge potential in Europe for the reasons I mentioned, in terms of how interpretation can help prevent offences.

“To this day, it is a challenge to create an understanding of why we need interpretation. Yet an appreciative interpretation is actually the basis of all protected areas.”

Thorsten Ludwig, Interpretation trainer and planner

Thorsten: The fact that interpretation is so uncommon in Europe compared to the USA is certainly largely due to the fact that the method originated there. Interpretation has been introduced in the US National Park Service since 1940 and has its own department and training centres. In Germany, for example, there were around 20 environmental education concepts at the beginning of the 1990s, when we started with ‘Bildungswerk interpretation‘, which influenced the work in the protected areas. To this day, it is a challenge to create an understanding of why we need interpretation on top of everything else. Yet appreciative interpretation is actually what underlies all protected areas. This is where we could work together more closely at European level: We have a good co-operation with the Europarc Federation, and the European Ranger Federation could also work on longer-term capacity building. But for this to happen, the protected area administrations in Europe must be prepared to organise such further training.

Urs: I always try to make it clear to my colleagues that interpretation is not about imposing yet another method on the rangers. It’s the other way round: interpretation is our own technique, our own language, because it has been developed from the bottom up by our colleagues in the USA. I hope that I can make this clear to my branch, also by doing a training course in interpretation in the near future, so that I can train from ranger to ranger.

“Interpretation is not about imposing yet another method on rangers. It’s our own technique and language, because it has been developed from the bottom up by our colleagues in the USA.”

Urs Wegmann, Swiss ranger and Certified Interpretive Guide

How can rangers learn more about Nature Interpretation on their own initiative?

Thorsten: All our courses are documented on the Interpret Europe website. For example, we have a 40-hour certification course to become a Certified Interpretive Guide. But of course it is not always the best option to organise Europe-wide courses due to the distance to the training locations. That’s why the protected area administrations usually organise courses for their region themselves through us. We can organise the Certified Interpretive Guide in 19 languages, for example. And if Urs is a trainer, the protected areas can also write to him directly, just like any other IE trainer. You can find an overview of our licensed trainers throughout Europe on our website.

© header photo: Thorsten Ludwig

editorial work for this

content is supported by