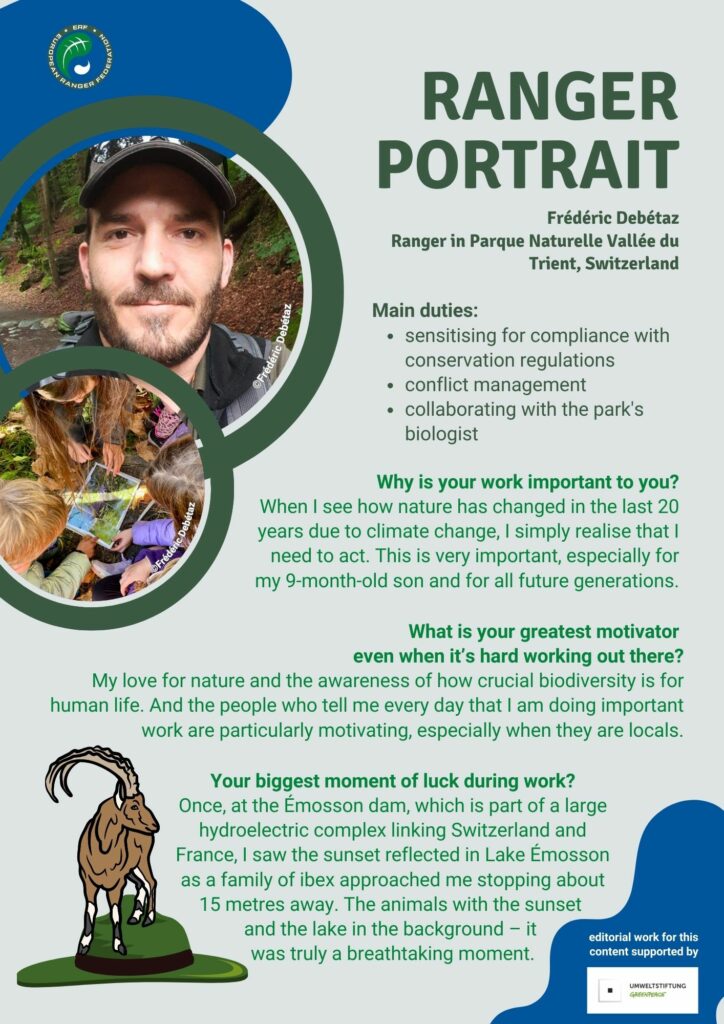

Ranger Frédéric Debétaz works in the brand new Trient Valley Regional Nature Park in the Swiss canton of Valais. Although the local population has been involved from the outset and democratically agreed to the park continuing beyond the candidate phase, there is still a lot to do for the Park’s team and the rangers accompanying them. Read how patience and respect are key tools.

For conservation concepts to be effective in natural habitats and for emblematic species such as the black grouse, the lynx, the badger and the many other species in this diverse region, some rules and guidelines are needed. In this interview, Frédéric tells us about his work: fostering good conduct from visitors in nature and creating understanding for possible restrictions.

Frédéric, can you give us a brief insight into how you came to be a ranger?

At first, I was a lumberjack. But as I worked in the forests, I saw more and more signs that the situation was deteriorating, including the repeated droughts that have worsened in recent years. So I wanted to do something about it to secure the future of our children. I first joined the Youth and Nature initiative of the Swiss nature conservation organisation Pro Natura and since then I have been taking young people, mainly children, out into nature one weekend a month. But my dream had always been to become a ranger. The only problem was that this profession didn’t yet exist in Switzerland when I was thinking about my career. It was only recently that I discovered that there was finally a training programme for rangers in my region. For health reasons, I had to give up my old job anyway, so I enrolled in this ranger school.

So how did your first ranger job come about?

A new park was recently established near my home: the Trient Valley Regional Nature Park in the canton of Valais. I had been observing behaviour that is harmful to local flora and fauna in the forests for a long time. So I contacted the park administration to inform them about these activities, which I kept coming across while photographing nature. One day they contacted me and other rangers in the region and told me that there might be an opportunity for me.

‘Last year, we analysed the coexistence between visitors and nature. We identified a number of problems: wild camping, loose dogs, littering, etc. In around 500 conversations, we were able to effectively raise awareness, as most were not aware of their inappropriate behaviour.’

The regional nature parks often call on the rangers to take part in awareness-raising projects. Last year, five of us ‘nature guides’ were out in the field for ten weeks investigating the coexistence between visitors and nature. We identified a number of problems in some parts of the park: wild camping, loose dogs, littering, etc. In around 500 conversations with the various visitors we met, we were able to effectively raise awareness among most of them, who were generally unaware of their inappropriate behaviour.

Which role do communication and conflict management play in this?

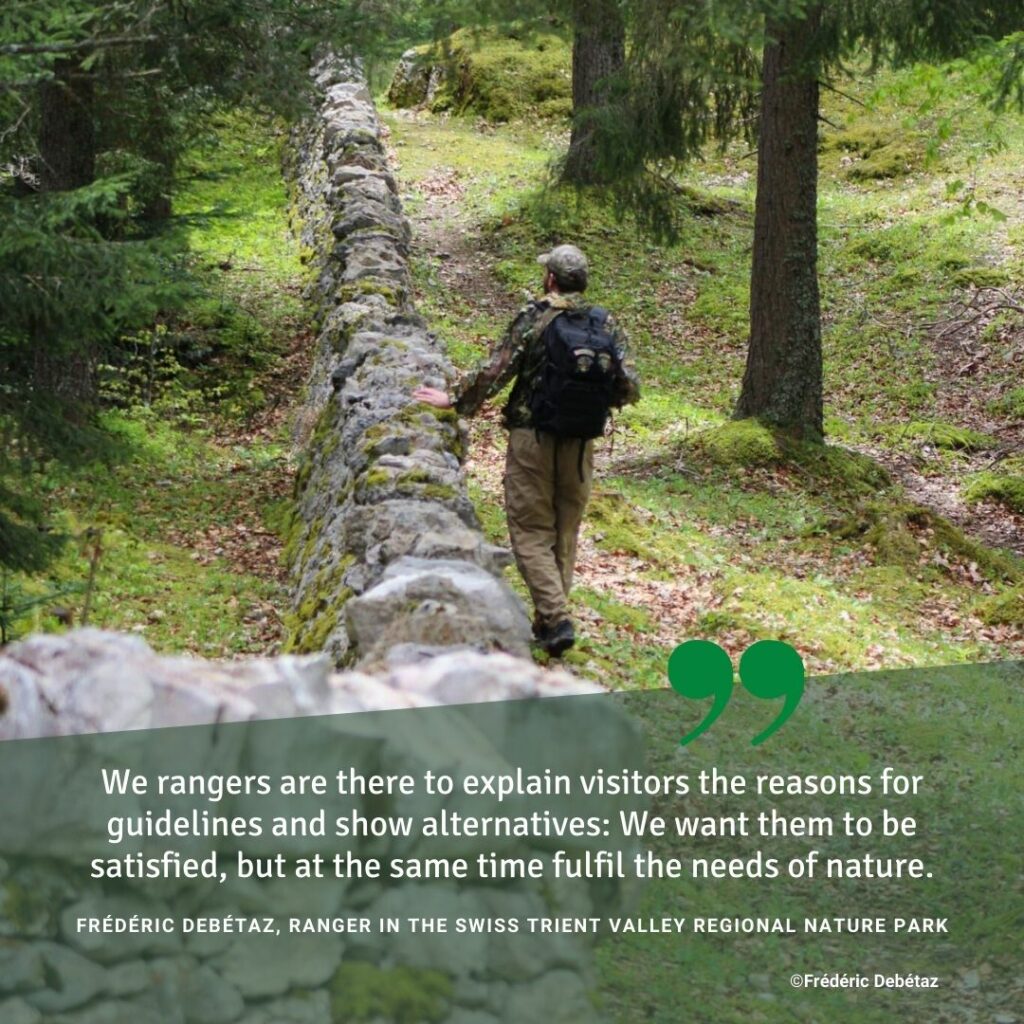

From the obligation to keep dogs on a lead to the exclusive use of the official toilets, there are many rules and guidelines that visitors should observe. Most of these are based on common sense, which not everyone may realise. We rangers are there to explain to park visitors the reasons for such guidelines, but also to point out alternative solutions: We want them to be satisfied with their visit in the end, but at the same time we want to fulfil the needs of nature conservation. In this way, people remain open to the good practices we want to communicate to them – a win-win situation. To achieve this, we receive excellent teaching on conflict management at the ranger school and learn the rules of peaceful communication. A ranger should be able to avoid escalation and find solutions that benefit both sides. For me, this is the most important tool in a ranger’s life.

From your own experience: What works best to de-escalate a conflict?

Firstly, you have to know yourself, control your reactions and stay calm. The second point is that you must always respect people. If they sense your respect, they will behave more co-operatively – even if there are long discussions and we still end up with different opinions. Fortunately, people rarely become aggressive. One of the problems is that old habits persist. For example, some locals are used to walking their dogs and not picking up their droppings or camping next to a lake. Our job is to remind them that this is not – and never has been – allowed. With the increase in tourism in the Alps, we are under pressure to adhere more closely to these rules. Many were frustrated at first, but after we took the time to explain the reasons for these rules and why they apply here, people usually play along.

How do you involve locals and encourage good behaviour in nature?

The Park works with farmers, tourist offices, hut owners and other local stakeholders. The rangers are the eyes in the field. For example, farmers have asked the park to make dog owners aware that dog faeces on their pastures can cause serious health problems for their cattle.

The Park relies on the contribution of local people to preserve its nature, culture and landscape: Every four years, citizens are invited to submit project ideas to the administration. Currently, there are around 40 projects for the next four years, in which also rangers are involved.

But the Park itself also relies on the contribution of local people to preserve its nature, culture and landscape: Every four years, citizens are invited to submit project ideas to the administration, which are then assessed for feasibility. Currently, the Park has around 40 projects of this kind for the next four years, in which we rangers are involved whenever we are asked to help. For example, the park is currently running a project with the ranger school to reconcile winter sports and the conservation of the emblematic black grouse. Skiers, for instance, are not aware that they are compromising the survival of this bird when they ski in the designated ski areas. We are also counting on the locals, who have helped to sensitise winter sports enthusiasts and protect the animals.

So the locals are largely in favour of the new Park?

The seven municipalities in the park were jointly recognised as candidates for the establishment of a regional nature park of national importance in 2020. To confirm the status in the long term, the population must be willing to commit to the preservation of nature, landscape and culture by initiating projects, participating in events and occasionally volunteering. In summer 2024, as part of a participatory and democratic approach on which the process is based, citizens were asked whether they accepted the permanent establishment of the park: 84 percent answered ‘yes’. Nevertheless, the daily work of a ranger convincing people to adhere to rules and guidelines of good practice in nature is fascinating, but certainly demanding.

What is your greatest success?

It is indeed often a challenge to be patient when people do not follow the rules or guidelines and to explain to them again and again why these rules are so important. But sometimes my work is also very rewarding. In the forest where I normally work, for example, people now know and accept that they have to keep their dogs on a lead to avoid disturbing wildlife.

©header photo: Frédéric Debétaz

editorial work for this

content is supported by