“Everything is a story” is the motto of Bo Storm, Danish ranger and certified Nature Interpreter. In our Nature Interpretation Training, he and his colleagues taught 15 rangers from 9 countries how important a good story is for their work. For three days it was all about storytelling techniques. The goal: involve people and make them support conservation in a way that no prohibition sign or purely fact-based argumentation can achieve. Now join us on a journey to Northern Denmark.

Startled giggles come from the group when Simon Christiansen puts the robin upside down into a cup. “17.6 grams, 4 of which are fat,” he reads from the scales and contently holds the little bird head up again in his hand: “With the fat reserve, it will surely continue its flight south today.” Simon is nature interpreter and warden at the bird station of Skagen Odde reserve on the northern tip of Denmark. There, where the North Sea and the Baltic Sea meet, a lot of migratory birds are already on the move at around zero degrees when 15 rangers from eight European countries and Israel visit at the end of March.

They are participants in our Nature Interpretation Training, hosted by the rangers of naturvejleder.dk. For three days, the group is travelling in the region of Frederikshavn to learn from their Danish colleagues how to teach people about nature. “It’s all about telling stories,” says training leader Bo Storm. “Because everyone likes to hear good stories” – unlike bans or lectures about the disastrous state of nature, as every ranger has probably experienced. Those who are touched by a good story want to contribute to its positive outcome and support the heroes of the story. These can be robins, but just as well dunes, trees or all other species and habitats. But how does it work: telling good stories?

Up to 9,000 birds pass through the ringing station with their stories every year

Simon blows aside the fluff on the robin’s belly. The skin underneath is almost transparent, the yellow fat clearly visible, as are the dark outlines of the liver. While he is ringing this specimen with information on where it was found, elsewhere in the bird station migratory birds from all over the world are coming into the net. “Today we’ve had birds with us that have been ringed in Iceland or even China.” Many have to replenish their fat reserves for the onward flight before setting off on a tedious journey affected by human light sources. “The birds are attracted to brightly lit cities,” explains Nature Interpreter. This means detours that can melt fat reserves faster. Sometimes death by exhaustion comes faster than the destination.

The robin, the chaffinch and the blackbird in the hands of Simon and the volunteers, students from England, Israel and Germany, are probably scared to death at this moment, too. “But such small birds forget again very quickly, unlike ravens. They have too good a memory, but they are also too clever to get into our net,” says the ranger and releases the bird with a wave of his hand. So it is rather the small birds whose ringing not only interprets flight routes, but whose stomach contents and plumage also provide information about plastic pollution in their path. The rangers and their helpers at the Skage Odde bird station ring between 6,000 and 9,000 birds a year. At least as many stories pass through their hands.

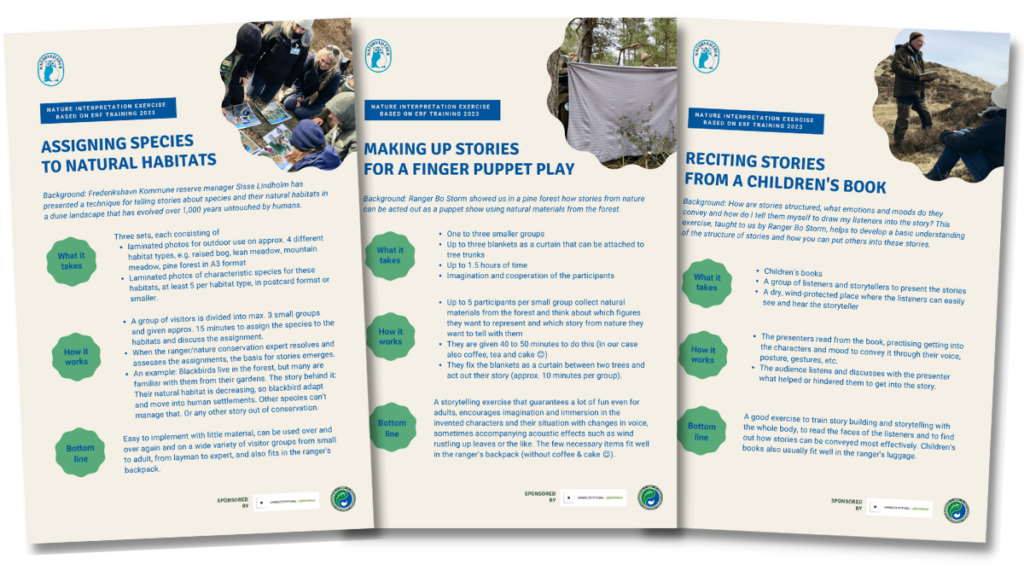

NATURE INTERPRETATION EXERCISES FOR PRACTICE

Want to apply the storytelling technique in your protected area?

Here are a few of the exercises that you can practise with colleagues or visitors.

The art of storytelling: full immersion in their heroes

This immersion in the stories of creatures, landscapes, buildings, works of art and people is something the participants observe, practice and discuss again and again. This is the art of the good story: immersing oneself as completely as possible in the perspective of the bearers of the story in order to be able to take the listeners along with them.

“Good stories are everywhere,” says Bo. He has been a forester and ranger for 37 years and, as a Nature Interpreter, has taught the nature and cultural history of his area to countless groups of visitors to the Bangsbo Reserve southwest of Frederikshavn. As in so many European countries where there is hardly any untouched nature left, the two subjects cannot be separated. And so the 15 rangers of the training practise storytelling not only in a mixed pine forest near the shifting sand dune Råbjerg Mile, in a 1,000-year-old dune-marshland ecosystem untouched by humans north of it, or in Lille Vildmose, the largest remaining raised bog in the European northwest southwest of Aalborg.

Rangers train to bridge distances for the connection of people and nature

They also immerse themselves in the stories of paintings or a Viking shipwreck at the Bangsbo Museum and let Bo take them back more than 3,000 years to the Bronze Age, when an ancient form of bronze horn, the lur, was played in Denmark and, in the face of increasingly cold temperatures, sacrificed along with the most beautiful women as the most valuable possession. They crawl back duck-walk-wise some 5,000 years to a Stone Age tomb and prepare their own dinner from pheasants freshly shot by ranger Jakob Konnerup – just as people have done since time immemorial before the development of the slaughter industry. They meet a group of children at the Lille Vildmose visitor centre with ranger Camilla Jensen and learn how children tell stories with their unbiased view of nature. In short, they train how to bridge distances, discuss people’s alienation from nature and learn how to reconnect them. Because only when people see themselves as part of nature and support its protection will nature conservation really succeed.

At the end of the three training days with all these small and big adventures and lots of cake organised by Bo and the Danish colleagues, it is hard to say goodbye. But the anticipation of putting what they have learned into practice is at least as great: “I can’t wait to tell stories back home in my area,” says Ranger Matt from England, for example. And for Lucia from Romania, it was straight into the full swing: “I have a group of children with us at the visitor centre on Monday. I can put what I’ve learned into practice right away.” So children in Retezat National Park got to learn about habitats and species just like in the exercise you find above to download.

Nature Interpretation is part of environmental management in Denmark

Denmark established a Nature Interpretation Service in 1987 as part of the environmental management. The aim is to apply and further develop Nature Interpretation methods that inspire people to care about nature and to develop a positive attitude towards sustainable living. In Denmark there is a network of about 350 certified Nature Interpreters. The Nature Interpretation Service works closely with the Danish Ministry of the Environment and the Danish Environmental Council and trains around 20 Nature Interpreters every year. Participants in this two-year training must already be professionally active, for example as a ranger. Nature Interpreters are employed by the state, municipalities or environmental organisations and wear the Nature Interpreter badge with the owl.

This content is sponsored by