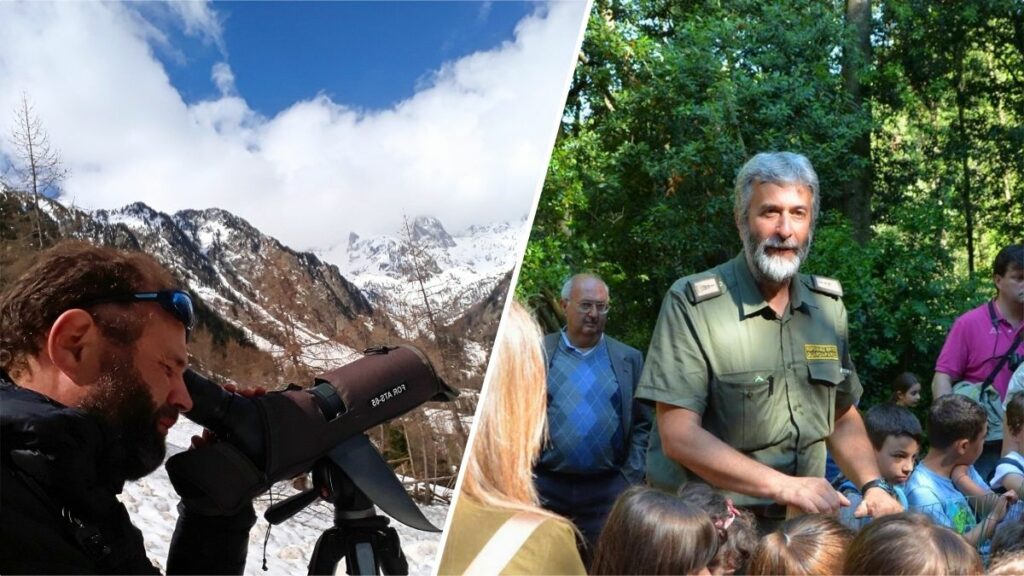

One looks after both: the wolf, still strictly protected in Europe, and the farmers in the national park, whose traditional alpine farming is directly affected by the wolves’ presence – ranger Romain Lacoste from the French Mercantour National Park works for coexistence. While Guido Baldi, ranger from the Italian Bracciano Martignano Nature Park, is managing the wild boar population to prevent damage to agriculture and protect smaller wildlife from the consequences of boar overpopulation.

“We must promote coexistence and also preserve the traditions and culture of the local communities in the national park”, Romain is convinced. And also Guido dedicates large parts of his ranger work to mediate between all the different interest groups in nature utilisation.

Two further examples of how important ranger work to mediate between people and nature already is and will be even more so in the future in view of the global goal for nature conservation areas.

How I became a ranger and got involved in the project

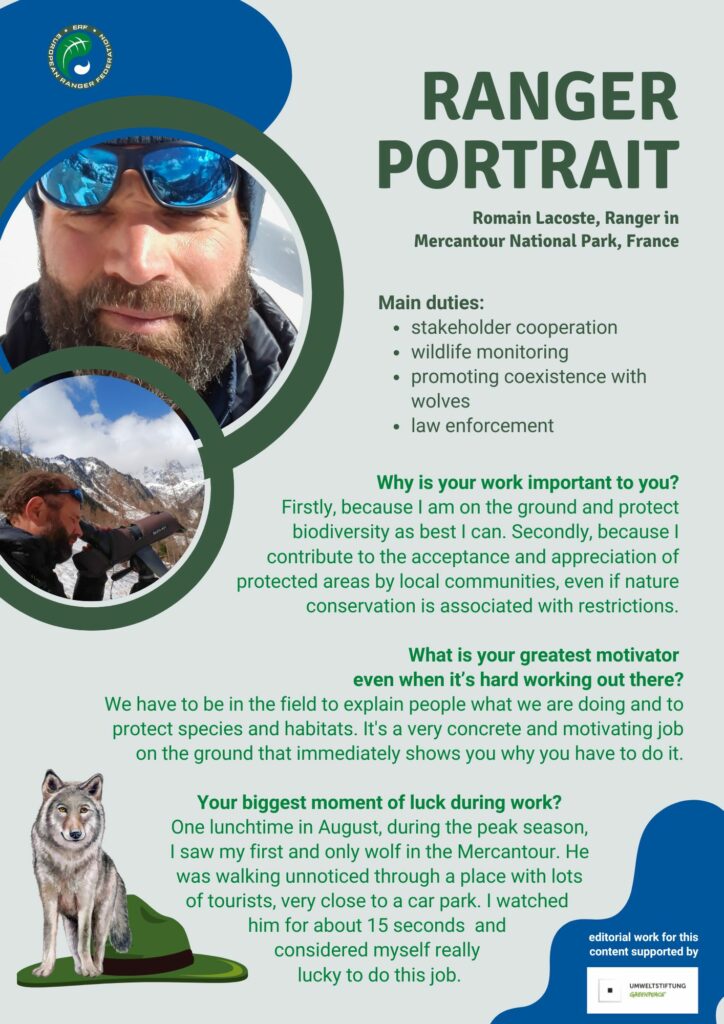

Romain

I am originally a veterinarian by profession and have been working in the field of primatology from a conservation perspective for many years. However, having realised that I could certainly make a greater impact by working in a larger ecosystem, I tried to enter the field of protected areas and found my current job in the Mercantour National Park in the southern part of the French Alps. Here I lead a team of four rangers and other staff in the Vesubie Valley territorial unit.

The wolf returned to France around 30 years ago. With the increase and spread of the population, especially in south-east France, the wolves’ presence has an impact on flocks, mainly sheep.

Large part of our work has to do with the coexistence of humans and wolves, which returned to France around 30 years ago. Since then, the population has increased and spread, especially here in south-east France. This also has an impact on the flocks, mainly on sheep. We rangers carry out scientific monitoring according to the national protocol to track the wolves’ movements and analyse their diet. And we work with farmers to help them cope with the wolf.

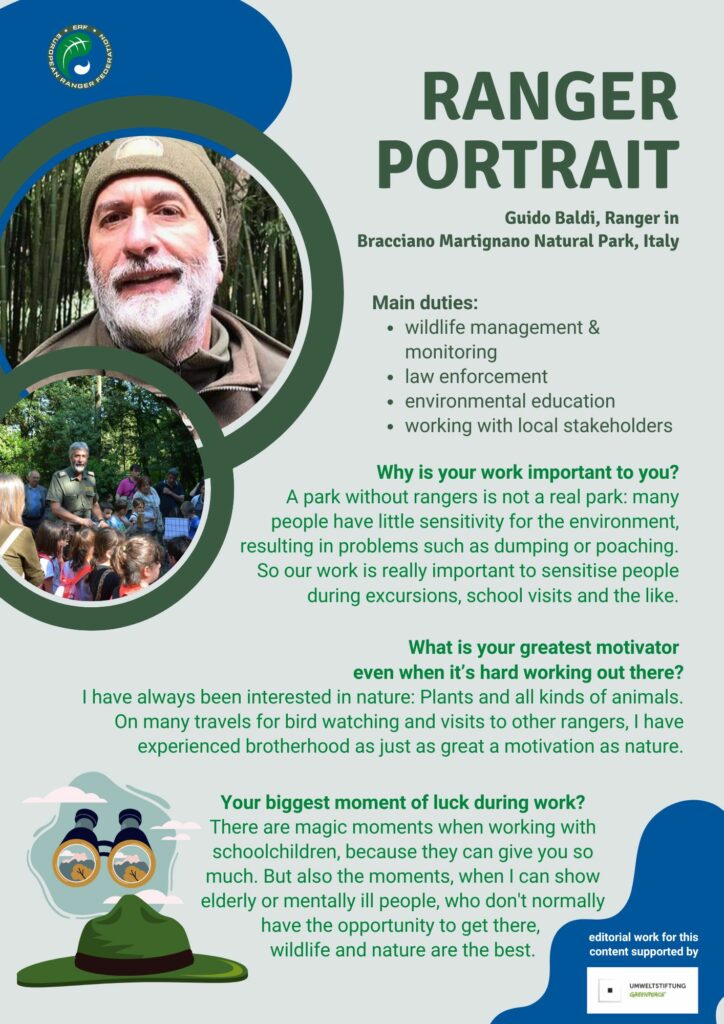

Guido

I have been a ranger since 1992 and have worked in various parks in the Lazio region for 26 years. Today I am a ranger in the Bracciano Martignano Regional Nature Park, which covers an area of around 17,000 hectares. From the very beginning, I have been involved in wildlife management, especially in controlling the wild boar population. We as rangers at my current workplace are involved in this, as hunting was banned in this park 25 years ago. Since then, the population has increased to an estimated 5,000 to 6,000 animals in the park.

What the Ranger project is about

Romain

In the area I manage, there are around 40 to 50 reported wolf attacks a year, covering around 300 square kilometres. As farmers in France receive compensation for each sheep killed by wolves after a certified expert like us rangers has confirmed a wolf kill, we go out into the field with the farmers to find the carcasses. We check whether ante mortem injuries have occurred and whether the damage is indicative of a typical wolf attack in terms of diameter, height and location of the wounds and other signs.

We also carry out monitoring, especially in winter. We use the snow to follow the wolves’ tracks. Several times a week we go to certain areas where we know the main routes. If we find a track, we follow it until we find genetic material that we can collect: mainly Faeces. From the number of tracks and camera traps we have set up in these areas, we can estimate how many wolves the pack currently has.

In summer, we are constantly present in the field, acting as interface between nature-oriented farming, including livestock guarding dogs, and visitors.

In the main season, in summer, we are constantly present in the field, acting as an interface between visitors and cows and sheep or, above all, livestock guarding dogs, both of which can behave aggressively towards humans. We promote understanding for the fact that the dogs have to be very precise in their protective behaviour, defending themselves against wolves but not against humans, explain to visitors how they should behave towards these dogs and what their work for nature-oriented farming is all about.

Guido

At the end of the Second World War, there were very few wild boar left, decimated by hunting or military action. After the war, the endemic wild boar population recovered, but not very quickly and the animals are rather small. Therefore, hunting organisations started to import wild boar from Northern Europe, which are usually larger and migrate more. Another problem was hybridisation by pigs that escaped from farms and mated with the wild boar. So the population grew and grew. While hunting controlled this in the past, the number of hunters themselves declined very quickly, from 2.5 million hunters in the 1970s to less than half a million today. At the same time, the wolf population has also increased. We estimate that there are 30 to 40 wolves living in our park – we track the population with the help of radio transmission. But even though our monitoring shows that some wolves feed on up to 80 per cent wild boar, they have no impact on the population because it’s just too big.

We rangers are responsible for controlling the wild boar population and work on prevention by erecting fences and even training farmers on how to catch the wild boars themselves.

So we rangers are responsible for controlling the wild boar population, especially to prevent damage to agriculture. We catch them alive with about 25 special cages, ranging from larger corrals to one-animal cages, and sell them to special organisations for breeding, but only in fenced areas as it is illegal to release them in Italy. We also mark the wild boars with tags containing the animal’s number and the park’s code so that they can be identified if they move outside our territory. And as the park is responsible for compensating the affected farmers, we work on prevention by erecting fences and even training some of them on how to catch and sell wild boar themselves.

Challenges, first outcomes and goals

Romain

We must promote coexistence and also preserve the traditions and culture of the local communities in the national park. To do this, we have the challenge of protecting the very specific agricultural activities in the mountains and looking after protected species such as the wolf.

So the main part of our work is social: we need to take the time to be on the ground to understand the lives of the farmers and the problems they face. We also need to support them and offer solutions, such as compensation after wolf culls. Our work to raise awareness and acceptance of livestock guarding dogs and respect for their owners with their traditional, nature-friendly agriculture, is highly appreciated by farmers and local communities. Finally, this is also an issue we are working on with farmers as part of a Natura 2000 project that promotes the sustainable use of resources. It is understandable that they need time to accept the presence of the national park, which was established 45 years ago and includes regulations to limit the impact of agriculture. But over the years we have built up a good relationship with most of the farmers.

Guido

We started in 2016 and up to this year we have caught around 2,000 animals since then. To estimate the actual number of the population, we use an index of animals caught per night. In 2016 it was 2.4 animals, now it’s about 1.5, so the population has most likely declined. At the moment, African swine fever is a challenge for us, preventing us from moving the wild boar out of the park. Although there has been no known case in our park so far, we are close to the Rome region, where 50 cases have already been documented.

I actually became a ranger to protect wildlife, now I have to control it – that’s my biggest challenge. But knowing that I am helping smaller mammals, amphibians or reptiles helps me.

However, the biggest challenge for me, who became a ranger to protect the wildlife, is to control it. But over the years, you learn that there are imbalances in nature such as the overpopulation of wild boar, which endangers the populations of smaller mammals, amphibians or reptiles. So we control one species to protect many others. In doing so, we work with farmers and the local police, but sometimes we have problems with hunters who would prefer us to hunt the wild boar as their development also affects the population outside the park. And there are people who are very sensitive to the suffering of the animals. We have explained in detail why we do what we do, but some don’t agree. In the end, we as rangers are standing between all these interest groups.

editorial work for this

content is supported by