One helps people with refugee background to find access to nature. The other coordinates a cadaver research project in a national park. Two projects, one profession: Hayden Bridgeman and David Moore are rangers. In their projects, both make an important contribution to a life worth living in our society: through social cohesion and through biodiversity as one of the pillars that sustain life on this planet.

Read our double portrait of Hayden from the New Forest National Park in England and David from Germany’s Hunsrück-Hochwald National Park, how they came to their profession and project and what goals they associate with it.

How I became a ranger and got involved in the project

Hayden

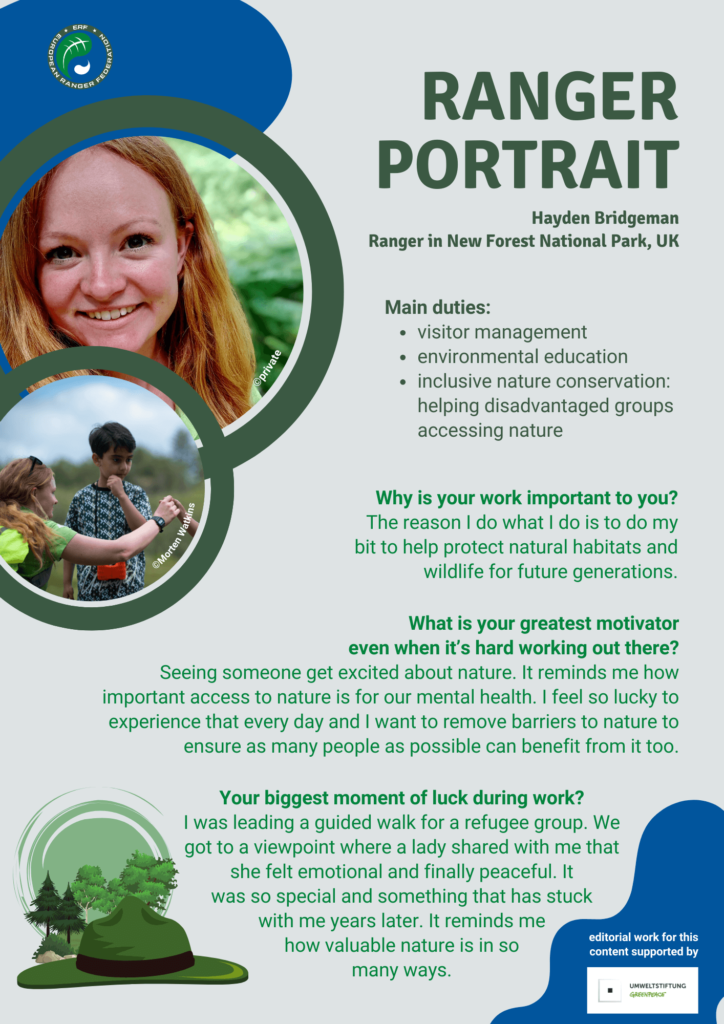

I became a ranger quite late on. I first studied photography, but I hadn’t found my passion there. So I started volunteering on various conservation projects abroad, including in Malaysia and the Caribbean. This really opened my eyes to conservation and that you can get paid to protect the environment. I retrained as a ranger in the New Forest National Park, where I later started an inclusive conservation project working with under-represented communities. I’ve been lucky enough to experience very welcoming people when I’ve been abroad, so I want to repay this by sharing the wonderful nature we have with people who may feel it is not for them or don’t have the means to utilise it.

I connected with local refugee communities and applied for a grant to research inclusive projects

This is how the “Inclusive green spaces” project came about in our national park. First I have been connecting with local refugee communities and charities to see what we could do to help these people reap the benefits of nature. With the idea of bringing it to them, we started offering guided walks or bike rides in the forests near them. At the same time, I applied for a scholarship from the Europarc Federation to learn from similar inclusive conservation projects across Europe. And I won it!

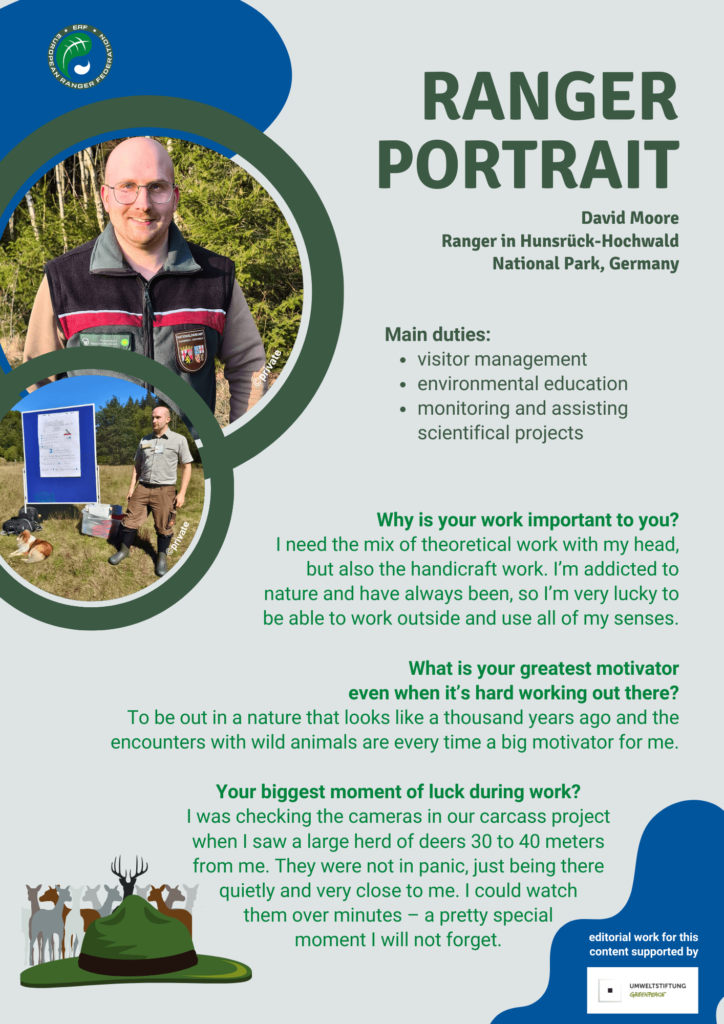

David

I actually became a ranger because I wanted to turn my passion and enthusiasm for nature into my job. While I was studying bioengineering, I realised that it wasn’t something I wanted to do for the rest of my life. Through my studies, however, I came into contact with national parks and learnt about the profession of ranger. It was this mixture of a hands-on work outdoors in nature or with visitors and scientific work that convinced me.

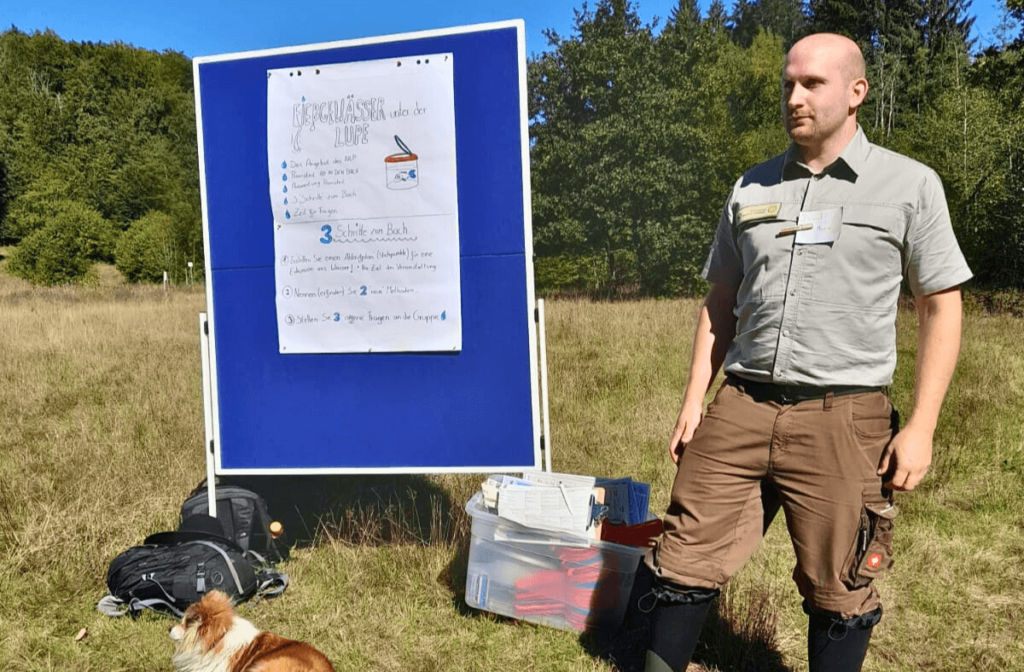

I had the opportunity to take over organisation, coordination and field work for the carcass project

Now I am not only a ranger, but also work in the research department of our park. In my double role as a research assistant and ranger, I had the opportunity to take over the organisation and coordination with the partners, but also the field work for the nationwide carcass research project in our national park: organising, setting and attaching the photo trap cameras, deploying the carcasses as research objects at fixed points – the complete organisation from start to finish.

This is what the Ranger project is about

Hayden

Although access to nature helps mental health, I feel that those who need it most can’t access it. This is what I wanted to change by starting the project of inclusive green spaces for the refugee community in our park. Meanwhile we have guided walks or cycle tours also in our national park. My task is the overall coordination to help the charities bringing the target group by public transport, while we pick them up at the station and provide picnic lunches.

Last year, we had about 20 visits to our national park with various charities. Overall it’s all about spending quality time in nature and doing mindfulness work. But it’s also about creating that community in the sense of friendship and providing a safe space to be as a basis for integration into the local community.

David

The project is called “Leaving wild animal carcasses in the landscape” and is being led by the University of Würzburg. Our national park is one of the national parks of the project and is responsible for it on a local base with a standardised setting across all 16 national parks in Germany.

The carcasses are all road-kills, which we collect and freeze until we need them. Once we have laid them out, we check them regularly, for example by taking samples. The function of the camera traps must also be monitored.

This monthly deployment of the research objects and the monitoring has now been running for four years. The background to this is that carcass research has been very neglected to date. As a result, there is a lack of experience and reliable data on the main carrion users, their behaviour, duration of use and visitor frequency at the carcass. As rangers, we in particular have the opportunity to raise the issue of carcass abandonment with visitors and the media to increase understanding of how important carcasses are for biodiversity.

Challenges, first outcomes and goals

Hayden

One of the main challenges is accessing the refugees. So we are lucky to cooperate with the charities that support us. Another is this community not feeling welcome in the UK. I really want to change that and hope the project helps make them feel at home and agree that nature is as much for them as for any of us. And of course there is the language barrier. We mostly find people who translate among the groups, but definitely hope to be able to fund a translator to come out with us for this project.

Some even say they are completely different persons since they stepped into the national park

We are also aiming to keep the project going beyond the funding and to have an apprentice ranger from a refugee background. And we see good results, for example the same people coming back on a visit as they are growing confident and talk to the charity. Some even say they are completely different persons since they stepped into the national park or as free as the ponies, that we have as free-range livestock. It’s such a rewarding experience to see that they too can enjoy what I can every day. And we have a long waiting list with people wanting to come over.

David

We had a few spectacular sightings in the carcass project: For example we sighted endangered species that fed on the cadavers such as pine marten or wild cat in our park, in the Eifel vultures were spotted, lynxes were reported from the Black Forest and a sea eagle from the Wadden Sea. That’s the thing we have to show: how important it is to understand more about the valuable resource a carcass is. And how we deprive the ecosystem of its much needed biomass when we keep taking cadavers out of nature. Leaving them is of big importance for biodiversity.

In the end, it is about how we deal with the valuable resource of carrion and its importance for biodiversity in the future

Gaining acceptance for this is the big challenge: On the one hand there are people who find it disgusting or fear epidemics, though the project strongly indicates that an intact decomposition species community is the best protection against epidemics. On the other hand, some people with a background in hunting are sceptical as our project means less game meat. In the face of this opposition, we have to see the carcass research project through for the planned research period of another four years. In the end it is about nothing less than the question of how we deal with the valuable resource of carrion and its importance for biodiversity in the future.

editorial work for this

content is supported by