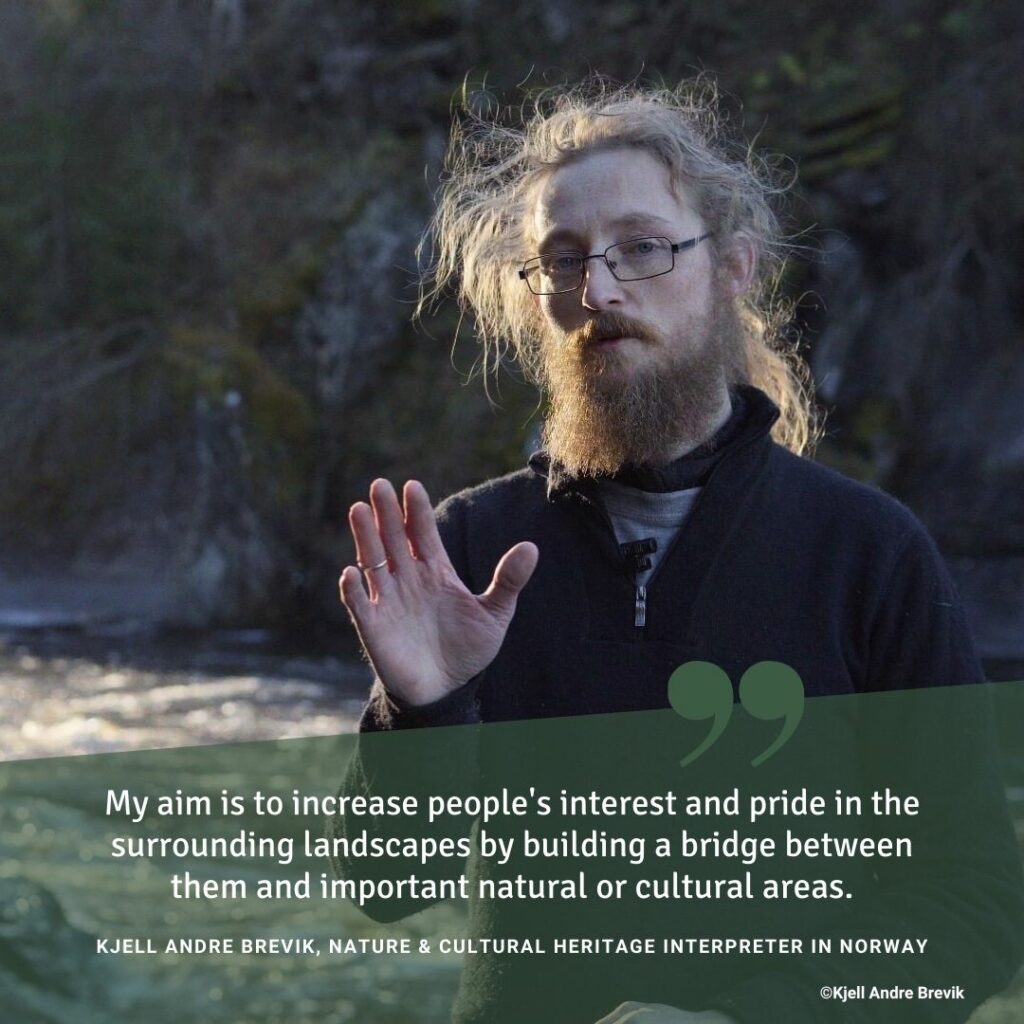

To give people a deeper, personal meaning of nature and its phenomena: What was once the hobby of archaeologist Kjell Andre Brevik is now his profession. As nature and cultural heritage interpreter in the Trøndelag region of central Norway, he takes young and old outdoors, whether to old trees or ancient rock art. And usually leaves them with a new connection to nature to take into their everyday lives.

Kjell grew up on the coast of Trøndelag in a varied natural environment with sea and mountains. Himself fascinated by the natural and historical places in this landscape and their stories, he hopes as a heritage interpreter to gradually play his part in helping civilisations take a more nature-friendly direction.

Kjell, please tell us how you came to work as a natural and cultural heritage interpreter.

During my studies, I discovered that I was very eager to disseminate information by taking groups out and letting them experience spaces and phenomena. I saw how nature and culture are an integral part of life. As my experience grew, I realised that I could also bring this to my region. While working at the museum and as an archaeologist, I always remained keen to talk about it. So I attended a Certified Interpretive Guide (CIG) course in the spring of 2023. It was offered by the Norwegian Regional Parks and Interpret Europe.

At that time, I was working at the public library in Melhus, where I ran some projects taking youth and adults into the landscape to connect literature and citizen science. After my participation in the CIG, I got a job in Melhus municipality, which is based at the open-air museum on the one hand and the library on the other. My job is to take people out and integrate nature and heritage tours into my library work to connect people with phenomena – either in literature or in nature.

Which are your concrete goals by doing Interpretation?

My aim is to increase people’s interest and pride in the landscapes around them by building a bridge between locals or tourists and significant natural or cultural areas. What particularly impressed me in my CIG course was one of the five claims to interpretation made by interpreter Thorsten Ludwig, former managing director of Interpret Europe: Offering pathways to deeper meaning.

‘I take groups of students on a ‘saga walk’ to get in touch with both oral traditions and concrete phenomena. This could be ants, an old tree or rock art – it’s about highlighting natural and cultural phenomena by engaging with the group to offer meanings that people can relate to.‘

For example, in one of the largest collections of rock art in our region, set in a natural corridor of great significance in times past. Every spring or early summer, I take groups of students on a ‘saga walk’ to get in touch with both oral traditions and concrete phenomena. This could be ants, an old tree or rock art – anything they are curious about. So I improvise as I communicate, highlighting natural and cultural phenomena by engaging with the group to offer meanings that people can relate to.

When they leave the place, I hope they can take some thoughts home with them to integrate into their lives. This can be anything from gardening to conversations with friends to projects at school. And indeed, many people tell me after the excursions how much they enjoyed being able to connect with the phenomena we talked about, observed, touched or smelled.

What are the biggest challenges you face when linking people with natural and cultural heritage?

Especially in this part of Norway, we don’t necessarily engage in dialogue without being strongly provoked. In some cases, the use of interpretive techniques doesn’t always help. It’s not easy to get people to talk, especially in groups where they are not acquainted with each other. Most of the time, it’s more scratching the surface in those cases, whereas I would like them to get involved in depth. And in general, we have a lot of nature in Norway – at least that’s what people think. But actually we are not so much connected to it anymore. Like most European civilisations, we are very technically oriented and prefer to spend our time indoors. So it may take some extra effort to sensitise people to natural phenomena.

Connecting people with nature: That is also rangers’ role. What parallels do you see?

I may be the only one doing heritage interpretation in Trøndelag. But from what I know about rangers in other regions, I find a lot of similarities between their tasks and my work. Both have the link between managing natural areas and heritage interpretation. Here at the museum, my team and I take care of the maintenance of the cultural heritage, such as maintaining the paths. So my work is about both: removing shrubs from the paths and getting people to manage a natural meadow themselves or making them interested in geosites that are protected for geological or geomorphological reasons.

What tips do you have for rangers and anyone interested in interpretive techniques?

We often have expert knowledge, and of course you have to know your participants: If there is a group of specialised, well-informed people on your topic, that is of course great. You can just go ahead with your knowledge and experience. But in most cases, I believe that less information and more the way you communicate is important. I know that now, because I was actually getting tired of my own way of disseminating information, of telling people basically everything about this forest, this bog, this archaeological site. But one of the main aims of interpretation is to get the essence out.

‘If you get people’s attention 20 percent of the time to get information across, you can fill the other 80 percent with meaning of natural phenomena for their personal life. So interpretive work will gradually move people in a more nature-friendly direction.‘

That’s my recommendation for rangers: get familiar with interpretation techniques to incorporate them into the way you’ve communicated information from the beginning, focussing on a dialogue with your group. If you get people’s attention 20 percent of the time to get information across, you can fill the other 80 percent with meaning of the natural phenomena in question, which they can later implement on their own property, in their own written work, in their own work with students or pupils. So I think this interpretive work with small groups will gradually move people in a more nature-friendly direction.

editorial work for this

content is supported by