In recent months, Europe has hosted two rangers travelling around the world: Kate and Charlie, originally national park rangers in England, have been working as volunteers with rangers throughout Europe since October. Practised ranger exchange, more or less far away from their home territory. Here, the two describe how they have experienced ranger work in Europe so far and their biggest learnings from their time on the road.

After a year of volunteering in various parts of the United States, Kate Dziubinska and Charlie Winchester began their European journey in Malta, where they worked with Camilla Appelgren and her colleagues from the Malta Ranger Unit (MRU). From there, they travelled on to Switzerland, where they spent a few weeks in each of three different protected areas in the country: “First, we worked with Ranger Silva in the Glaubenberg moorland near the town of Sarnen,” says Charlie. They then travelled to the Zurich region, where they worked as volunteers in the Greifensee area with Urs Wegmann, the former ERF President and then with the Griffin Rangers. Finally, the couple travelled with Alain Chambovey to various protected areas in the Basel region.

Open doors for the two volunteers at rangers’ houses in Europe

Kate and Charlie landed in Montenegro this month and stayed in Durmitor National Park until Christmas. “In the USA, protected areas have special programmes and financial support for volunteers who stay there for a longer period of time. It’s not quite so easy in Europe, so we tried to find accommodation with rangers,” says Charlie. And they found open doors with rangers who kindly offered to let them stay at their home.

We wanted to learn what the work of rangers around

the world looks like and be part of a larger ranger community

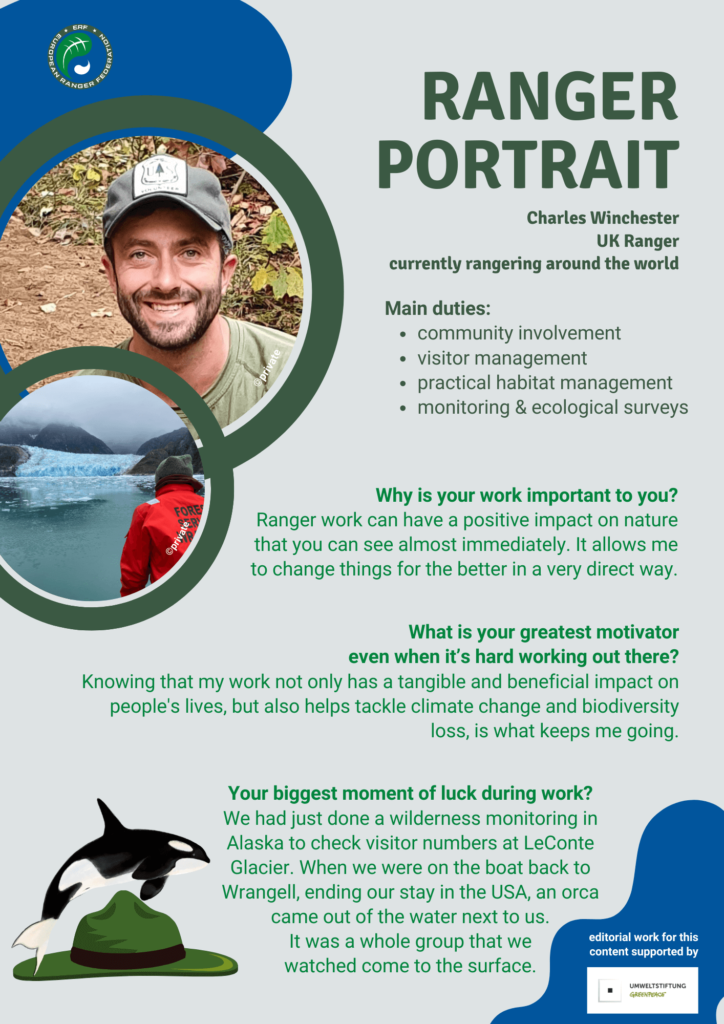

But how did the idea of travelling the world as a ranger come about in the first place? “We were rangers in the UK for five or six years. We worked for the South Downs National Park in the East of England and knew our role pretty well, dealing with people from different backgrounds, such as nature reserves, farmers, large landowners, local authorities and governments. This gave us the idea to learn what the work of rangers around the world looks like, because the role of the ranger is so diverse and depends on the ecosystem, the country, its government and much more,” explains Kate. “We also wanted to be part of a larger ranger community,” adds Charlie. So they started where it all began: in the United States, the cradle of what we know today as rangers.

Ranger work in Europe: learning from each other despite and because of similarities

On their way to Europe, the British rangers were curious about skills and approaches they could apply back home, as many European protected areas are similarly inhabited by humans. “We were very impressed by the experiences in the protected areas around Zurich. The way the rangers dealt with the people is what they call sensibilisation. It’s a term we’ve never heard before, but it really makes sense and describes how they deal with different people in different situations.”

Working with Junior Rangers in Switzerland is much about

having fun and teaching how to enjoy nature in a responsible way

Another approach to working with junior rangers caught their eye at Greifensee: “It was about teaching children about littering, pollution and the forest in autumn. While we are often fascinated by what we are teaching people and how we are getting information across in the UK, working with the Junior Rangers in Switzerland was much more about having fun and teaching how to enjoy nature in a responsible way. I think it’s a much nicer way,” summarises Kate. Raising awareness of nature among people who wouldn’t necessarily spend time in protected areas was a striking experience for the two at Zurich Airport: A corporate group attended a talk by a ranger about the species and processes of the relatively new protected area “The Circle”, which is located directly on the airport site.

People and Wildlife side by side: an example from Switzerland shows that it works

Also something that is transferable to the UK, according to Charlie, is the beaver reintroduction in Basel region. “There are a lot of concerns about beaver reintroduction in the UK, so it was very helpful to talk to Alain about a real-life example close to lots of people. It showed how people and wildlife can coexist with very little conflict. I think this is easily exaggerated until people know what it’s going to be like.”

They learnt about a much more difficult ranger job in Malta. “Apart from the fact that the Malta Ranger Unit is very new and is not officially supported as an NGO, I think the attitude towards nature in Malta is more difficult than in Switzerland,” says Charlie. Illegal bird hunting and trapping have a long history on the island. Environmental offenders and public institutions often seem to be intertwined, so that violations are not always prosecuted. But the MRU rangers keep reporting and posting on social media to highlight these offences.

Different attitudes towards nature and less support impedes rangering in Malta and Montenegro

“They have much more of an uphill battle to face,” concludes Charlie – like the rangers in Montenegro, according to their initial impression. “Although the rangers in Montenegro are even government employees, they have problems with funding and resources to do their job.” People in Montenegro also live in the protected areas and have practised activities such as hunting, which they are now restricted from doing: “I think that’s one reason for the rather negative perception of the rangers’ work.”

Of course, the two British rangers not only learn, but also bring their own experiences to the protected areas. “New ways of engaging with the public, bringing people into the protected areas in a responsible way, events or different kinds of people to engage with”, Kate lists a few. For example, there is the “Miles Without Stiles” programme, which brings people with physical or mental disabilities into nature and encourages them to discover it with very accessible programmes. “As part of this programme, we have also worked on the infrastructure so that people in wheelchairs can follow a circular route without obstacles – alone or with a ranger,” says Charlie.

Something that could also work well for one of the most visited places in Montenegro’s Durmitor National Park: The Black Lake and the hiking trail that circles it. “Given enough funding to flatten and widen it in some places, the national park could be opened up to people who perhaps think that national parks are not for them”, says Charlie. Combined with clear signposting and route maps, this access for all could reintroduce more groups of people to nature. And with it an understanding of its protection, which is just as important in Montenegro as it is in England, Malta, Switzerland and the rest of the world.

In how many parts of it the two will still be rangering, learning and inspiring others: They don’t know yet. But the next stops are clear: a two-week Christmas holiday with their families in the UK, then a flight to Kenya in the new year to a protected area on the outskirts of Mombasa and possibly other protected areas further inland. Then it’s off across the Indian Ocean to New Zealand and Australia.

editorial work for this

content is supported by